I’ve driven by this sign several hundred times over the last few decades. I’ve stopped to make pictures of it a few times as have countless others undoubtedly. I made this picture one Sunday a few weeks ago with a new-to-me camera after a long, but productive day of looking and listening and turning around and going back.

When I got the film and scans back, I settled in on this picture and thought about the times I’d seen it in the early morning fog, the driving rain, and when it was nearly invisible, blanketed in snow. I knew there was a name and phone number on the sign, but never paid it much mind.

Looking at the picture again yesterday, I picked up the phone and called the number. A man’s voice sang hello on the other end. “Mr. Bell?” I asked. It was, he said. I told him who I was and that I was calling to ask about the sign on US 119. For the next 10 minutes, Mr. Ed Bell, who is “88 and a half” proceeded to tell me about himself, his sign ministry, and about how wonderful it was to receive a phone call out of the blue about one of his signs.

He reckons this particular sign was put up about 20 years ago. If you’ll notice on the far left, you’ll see the initials “H.S.” Mr. Bell told me he dedicated the sign to his good friend Harlena Shepherd, who gave him $25 to help make the sign all those years ago.

He told me I could call him anytime. He said he was going to pray for me as soon as we got off the phone. “You’ve made my day. Thank you, young man,” he said as we hung up. Thank you, Mr. Bell.

Appalachia

Appalachia Photobook Friday - Expanded

In 2015, I started sharing photobooks about Appalachia via Instagram every Friday (well, almost every Friday). I wanted to use the photo-based social media platform to share some of the books from my collection and to sometimes deliver some brief thoughts about them. My collection isn't large by any means, but some of these books have had a profound impact on me as a photographer and as an Appalachian.

I love the tangible nature of books. Even today, with digital cameras, iPads, and everything being digital, I still prefer to read the paper, to handle prints, and to spend time with books, especially photobooks. There's something romantic to me about handling a book, spending time with it, noticing something on the third or fourth look that I missed on the first. Photographs live so differently in books that they do online or even on walls. There's something about the pace of looking through a book, being able to put it down and pick it up again that I find comforting and I connect with. Books are an art in of themselves.

In an effort to dig a bit deeper and formulate my thoughts a bit about each of these books, I plan to write a more in-depth, opinionated review here. Like the Appalachia Photobook Friday Instagram posts, I'll plan on publishing a review of each book on a Friday. My goal will be to keep the reviews under a thousand words, give or take, and to make this series available as a resource to anyone interested. In the interest of full disclosure, if books have been sent to me for review or as gifts, I'll state that clearly. I won't get anywhere near as in-depth as Jörg Colberg does over at Conscientious, but I'll be clear about my opinion and thoughts on each book.

I've been excited about the conversations started as result of me posting these books to Instagram. I'm also excited to discover new books, so if you'd like to recommend one, please do.

(Below is a screenshot of how the books appeared in my Instagram feed, but please note that I won't be posting reviews in any particular order.)

Seeing Appalachia | John Ryan Brubaker

I learned of John Ryan Brubaker's work through a mutual friend, Emma Fisher, Tamarack Artisan Foundation's program director. Before I even saw the work, I was taken by the process of the work. More and more these days, I'm interested in how work is made and after learning that John Ryan used acid mine drainage as a central component of his series 'On Confluence,' I wanted to learn more. John Ryan not only shares images from the series, but also images from the field as the work was made.

(Editor's note: for the last three and a half years, I've written the series titled 'Looking at Appalachia' here on my blog. Since launching the Looking at Appalachia project in February 2014, I've considered renaming this series to create a clear separation between my personal writing and the project. This installment is the first under the new series name 'Seeing Appalachia.' Thanks for reading and for your continued support.)

Now on to John Ryan's work. I asked him to introduce it and talk about his process a bit.

On Confluence Walks down the North Fork

The North Fork Blackwater River runs past Thomas, West Virginia before joining the Blackwater proper in the canyon downstream. Thomas developed as a coal town in the early 20th Century, but as the mines were abandoned they filled with water which continues to drain into the river today. The mine void currently covers 1100 acres and discharges an average of two million gallons of water per day into the North Fork. The drainage has a pH in the 3.0 – 5.0 range and contains heavy concentrations of iron and aluminum. This water dissolves heavy metals and creates acid mine drainage, which is detrimental to river ecosystems, rendering them generally unfit for life, recreation, or consumption.

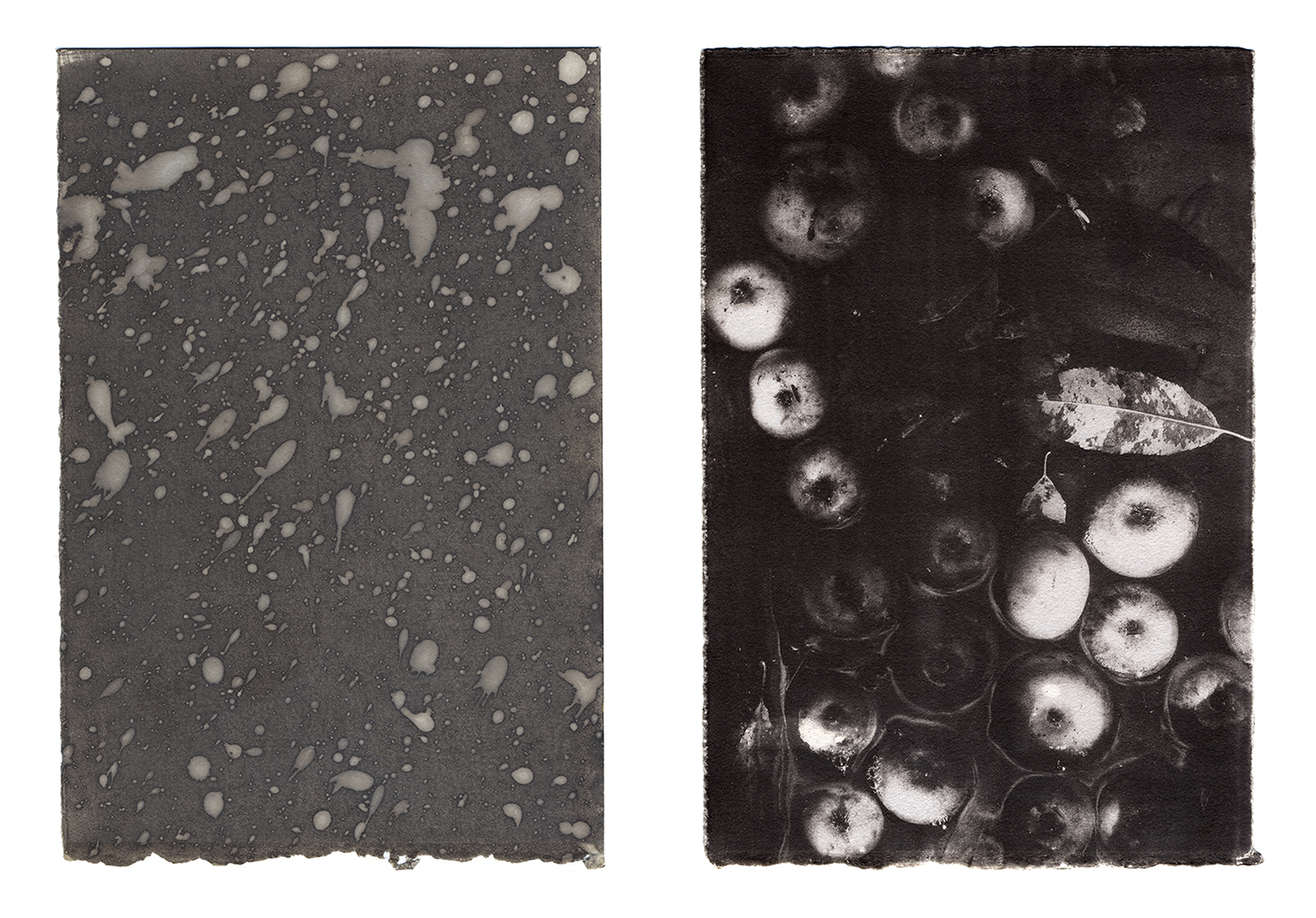

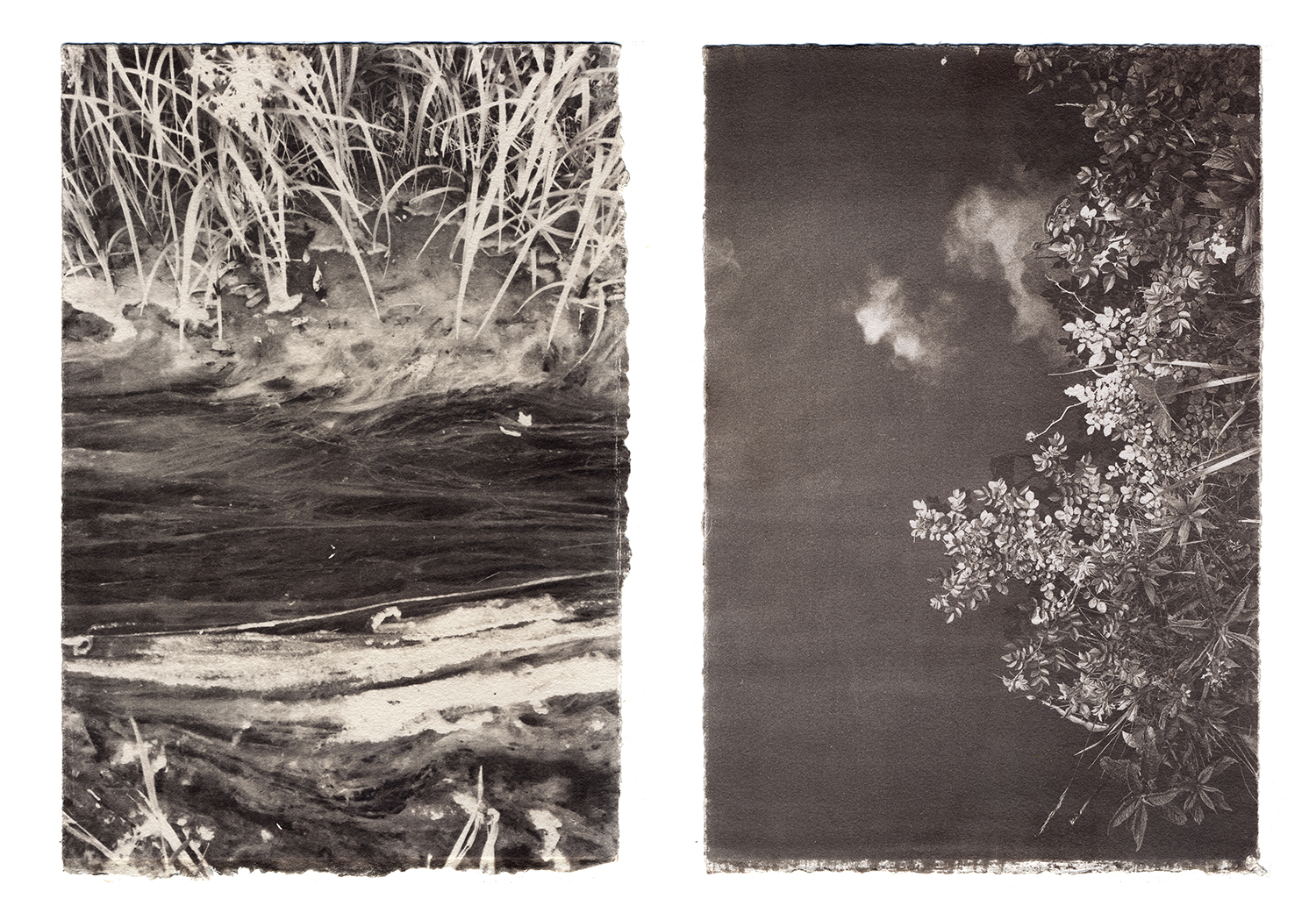

The images in this project were shot during a number of walks in and around the North Fork. As most of the river is difficult to access the process required walking through the riverbed directly. The prints were made using an iron-based photographic process called the Van Dyke Print. This process uses acidic water as its developing agent, making the contaminated portions of the North Fork an ideal location for creating prints.

The works, exhibited earlier this year for the first time at the Carnegie Hall Museum Gallery in Lewisburg, West Virginia, were processed directly in river water effected by acid mine drainage and have absorbed traces of the same heavy metals and mine runoff as the North Fork Watershed itself.

For the past four years I have split my time between the 500-person Appalachian town of Thomas, West Virginia and the million-person city of Brussels, Belgium. During that time the majority of my photographic work was shot and conceptualized in the urban environment and then printed and produced over the summer in my studio in Thomas. My recent projects, 'Maps for Getting Lost' and 'Every Path is Viable' deal with passageways, physical infrastructure and movement through urban space. They incorporate walking as artistic practice, GPS tracking and multi-exposure images of intersections and transit points. While considering a project based in the landscape of West Virginia I was drawn to the river as the organic, geographic equivalent to a transit grid. The lines created on the landscape by water are quite different than those carved out by public transportation and city streets, but they serve similar purposes for me artistically. They provide a fixed, finite space in which to move and observe with a camera.

By researching the history and route of the North Fork I began to understand the immensity of the damage done to this body of water. As is so often the case in West Virginia, the landscape here is scarred by resource extraction. Much of the river appears clear and healthy, with little sign of impact by mine drainage, but other sections are opaque and disconcerting shades of blue-grey or orange. I also became aware of its inaccessibility, as most of the shore is hidden within a dense growth of trees and uninviting thickets. After many failed attempts to follow the shore I decided to walk directly in the riverbed, submerging myself in the water and engaging with it physically as my subject. I consulted with local environmental experts to be sure the toxicity levels weren’t overtly dangerous to me. Ultimately, the photographs in this series were made on a number of day-long walks starting in the city of Thomas and ending at a waterfall downstream.

I chose to use the Van Dyke printing process for these works because it allowed me to work directly with the chemical nature of photography. It took months of experiments with chemistry, paper, exposure and negative density to reach the result I was after. I wanted the prints to absorb heavy metals from the water and to have a physical presence that is often lost in the presentation of photographs. A small run of the river with the ideal pH level served as my outdoor darkroom. I exposed the paper using the sun and developed the images directly in the river. The prints were fixed in a solution of sodium thiosulfate, returned to the river for rinsing and then dried on the shore. I'm curious how they will behave over time, but I've embraced the possibility of them shifting in color or density as they age. They are, after all, organic objects: paper, chemistry, water and light.

This project was supported by the Tamarack Artisan Foundation. It will be shown again in Thomas, WV in the Spring of 2016. You can see more of his work here and follow him on Instagram at @jrbrubaker.

All images © John Ryan Brubaker and are used with permission.

TAKING LIBERTIES, TAKING SHORTCUTS, AND TAKING ADVANTAGE OF PEOPLE

VICE sent two photographers to Appalachia and all we got are these cheap, damaging stereotypes?

In a recent interview, photographer Bruce Gilden said, “…you have to be sneaky to get the picture…” He said other things about respecting his subjects, his need to get very close and that only by veering into abstraction could he get closer. Let us not mistake being close for being sympathetic, though. Outside land-speculators came to Appalachia decades ago. They got so close as to tear into the land. Then they took it elsewhere … and sold it. Outside land-speculators had to be sneaky to get Appalachian coalfield landowners to sign away their mineral rights.

Taking a portrait, of course, is not an abuse on the same scale as taking land.But it is still taking. And just because Bruce Gilden’s in-your-face ambush approach works on bustling city streets doesn’t mean it flies elsewhere. Gilden speaks persuasively about his interactions with folk and stands behind — professionally and literally — his hard-flash and the caricature portraits that result. In some ways, I admire Gilden’s repeated defense of his controversial approach and his repeated willingness to field questions, but still I am not convinced and I don’t think I ever will be. Here’s why. People in different regions and of different histories have very different relationships to the camera and respond accordingly. Gilden’s one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t fit in Appalachia.

Gilden’s latest jaunt in the current issue of Vice (Vol. 22, No.7) is one of more than a dozen portfolios that make up the 2015 Vice Photo Issue. So, it’s worth noticing that Gilden’s portraits are not illustrations for a regular article; they were commissioned for an issue devoted to photography.

Shot over the weekend over June 6th/7th, the series titled “Two Days in Appalachia” includes congregants at the Kingdom Come’s Old Regular Baptist Church in Premium, KY, men at a prayer breakfast gathered at Covenant Mountain Mission Bible Camp in Jonesville, VA, and children and adults at the Harlan County Poke Sallet Festival. In the same issue is “There Ain’t No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down”, a series of images of church-goers in various Appalachian towns made by photographer Stacy Kranitz.

My assessment of Gilden, Kranitz, their guiding philosophies and work differs somewhat. My criticism of one doesn’t always apply to the other, but for the purposes of critiquing Vice’s decision to assign the two photographers jointly to the region and to run their work back to back, you may assume that my laments in this case apply generally to publication, editors and, yes, both photographers.

Screengrab from the online presentation of the 2015 Vice Photo Issue.

The 2015 Vice Photo Issue is,according to Vice photo editor Matthew Leifheit, “a testament to the enduring power of photography to understand the stories of our lives.” If only. Leifheit goes on to explain that his department teamed up with Magnum Photos by “sending out young photographers out on assignment together with Magnum members, other times emerging artists were influenced by the history of great photographers who have contributed to Magnum’s legacy. Although the approaches to documentation are diverse, we believe both established and emerging photographers benefit from sharing pages.” They also partnered with Magnum’s non-profit arm, Magnum Foundation, to share the work of their regional grantees.

Sending Kranitz and Gilden out together failed.

“The past few days have been hard,” wrote Kranitz on Instagram on June 7th. “I have been on assignment with another photographer, Bruce Gilden. He and I are at odds with the way we make our work. I watched him make portraits and aggressively enter my shot to get his own, while telling me ‘this is my shoot, you are just here’ I listened as he said disparaging things about people, I listened to his dissatisfaction with people being to [sic] ‘plain’ and late last night I could no longer stand by and continue to feel good about being bullied. He humiliated me in front of a group of church goers and I feel that I may have taken a stand at the wrong moment. That I was not being considerate or mindful of my surroundings either. I don’t hate Bruce or his work but I think turning people into what you want them to be, turning people into ‘self-portraits’ of yourself is complicated and dangerous especially in a place with a history of extraction.”

This principled and somewhat vulnerable reflection confirms everything I have thought about Gilden and his personality. It reflects some things I’ve come to learn about Kranitz. Kranitz deals, here and elsewhere, in introspection and flexibility of thought that Gilden never does.

My relationship with Kranitz is strained to say the least and the antipathy between us has been aired in public on occasion. Our commitment to dialogue about photography in Appalachia and our conviction of thought is matched. We’re both steadfast and that contributes to the friction between us.

I want to flag this history between Kranitz and I in order that I may follow-up and say that this article is not a witch-hunt directed at her. This article is a harsh criticism of an abusive project that was rushed, ill-advised and — given the ingredients — doomed to failure. As the liaison (producer?) for the project, Kranitz bears some of the responsibility. Mostly, though, I fault Vice.

A Recipe for Disaster and for Internet Buzz

Leifheit, Vice photo editor, never responded to my request for comment. Not knowing the specifics of the decision-making behind the Appalachia portfolios, I’m left to hazard a guess. GILDEN + KRANTIZ + APPALACHIA = CLICKBAIT, maybe?

By pairing Gilden (aggressive, abrasive, and loud-mouthed shooting style) with Kranitz (drug and alcohol-fueled Appalachia-is-one-big-off-camera-flash-shirtless-party style), Vice knew it was ordering fireworks, or cheap controversy, or both. Neither portfolio shows me anything new.Both reinforce the idea that Appalachia is somehow an exotic location for photographers to drop in and use people as props. They aren’t connected to any other purpose than being self-serving. In other words, they draw attention to the photographer more than the people and communities being photographed.

Gilden, here, substitutes Appalachians in to replace the nameless folks in his last set of portraits. Kranitz’s portfolio was made up, partly, of old images from existing series we’ve seen before. Gilden’s an old dog and you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Kranitz on the other hand iswrestling non-stop with her image-making, her presence, and the history of representation in Appalachia. Without wanting to sound patronizing, I think Kranitz is self-taught in new tricks — the more she learns the more she realizes she doesn’t know. She’s light years ahead of others, but as well as running rings around the pack she also makes wrong turns. Her Vice offering here is confused.

“I struggled with the complexity of translating the value and power of religion to urban populations, which have long participated in the characterization of rural people as simplistic and naive,” wrote Kranitz in her accompanying statement. Why does this need translation? And how does her series of images do anything to work against the characterization of rural people? We’ve all seen the visual tropes that cue the most widely known visual “facts” about Appalachia. What is it about this work that stretches us to see it differently? I appreciate Kranitz’s long-form work and commitment in the region, I believe she is on the verge of shifting to pursue something bigger than herself, but she keeps getting in the way.

Kranitz declined to speak with me for this article about this Vice assignment. She believes my decision to not invite her to serve on the board of Looking at Appalachia, an organization I founded, was an attempt to silence her voice. Since then, she has characterized me as running a“tyrannical crusade as gatekeeper of who can and cannot make work in the [Appalachia] region.” I disagree with her assessment of my work with Looking at Appalachia. I disagree that I’ve silenced her voice. I did not ask her to join Looking at Appalachia in an official capacity for reasons that I don’t care to make public.

Putting these things aside I realize this moment is a missed opportunity to speak with a young photographer with whom I (and Looking at Appalachia) share common concerns. I would not expect the same level of engaged conversation with others. Leifheit, I’d suggest, gave more time and consideration to his project PPIX, wherein he photographed things he peed on for 30 days than he did for Gilden’s “Two Days in Appalachia.”

Shut Down by Magnum, Ignored by Gilden

I suspect both Vice and Magnum both spent more time conceiving, planning, executing, and editing the Gilden assignment than he actually spent in Appalachia. Perhaps that’s the case sometimes if you’re a news agency on a tight deadline, reporting on time-sensitive issues. That’s hardly the case with this work. Why send Bruce Gilden to a part of the country that’s been visually stereotyped more often than not, to shoot in a style that, albeit bold, is incredibly impersonal and is stripped from nearly any context? Unfortunately, I cannot fully answer that question because despite a thoughtful and productive 45-minute telephone conversation with Cameron Cuchulainn, Magnum Photos Special Projects Manager, the follow-up email with specific questions I was requested to send, and sent, was met with zero response. Nothing. Zip. Later, I received a courtesy call from a reliable source who informed me the stonewalling was deliberate. I was shut down by Magnum. The fact that no one would respond in any official capacity to this type of work speaks volumes. I am beside myself, though I probably shouldn’t be, that an agency like Magnum would put their integrity, and that of its members, on the line in such a fantastically amateur way.

Am I saying that Gilden can’t or shouldn’t make work there? Absolutely not. But if he’s going to make work there, he can’t be the least bit surprised if there’s a strong negative response to his style of shooting and his presentation of these folks in an international magazine.

How is this work any different from the throngs of photographers who’ve made this sort of devoid-of-context work? Bruce, if you have an answer please get in touch; your studio manager said he passed my email along, but that was weeks ago. As with Magnum, I have no idea what you’re thinking.

It’s a slippery slope when you come to a region often misrepresented or only represented in a certain light, and use people as props. No amount of contrived language, heady MFA-speak, or artistic vision can make up for any of that. I don’t care what agency you work for. In the end, it’s the people who allow us into their lives that matter. People aren’t theories. We have no feedback from the people pictured. Will they receive copies of the magazine so they can see how they’re composed, framed, and displayed? Was it made clear who the photographers were on assignment for?

Vice catastrophically catapulted two headstrong photographers into Appalachia. Two different photographers, people, and approaches with unsurprisingly the same outcome.

There are photographers who want to be looked at and celebrated and there are photographers who want to see people and celebrate them through photography, in context, in a way that honors the people. Sadly, Gilden and Kranitz miss out on the latter — far more so Gilden than Kranitz. To Krantiz’s credit, she is devoted to making work in the region and spending lengthy blocks of time in Appalachia. I believe, like many of us, her work is evolving, but when I see it side-by-side Gilden’s in Vice presentation, I struggle to see a difference.

Appalachia is big enough for all of us to be making work that matters, work that can effect change — not only in us, but inside and outside the region. But this isn’t it. As they should, these images will be lost in the noise created by a media outlet more concerned with clicks and buzz than the people photographed in their stories.

More takers in a long line of takers.

(This article first appeared on Vantage on 31 July 2015.)

©Roger May, 2015. All rights reserved.