One of the things I’m most fond of is seeing how other photographers and artists work. If I see a picture of an artist in their studio or workspace, my attention is usually drawn to the background where I find myself looking at bookcases, work tables, and other “stuff” in their creative space. I also truly enjoy behind-the-scenes snippets of how they work and how things come together. In that vein, I wanted to share a bit about a book project I’ve been working on for some time now. It’s far from complete and very much an early draft. I have no publisher and real idea of the market interest in a book like this. There is still a good deal of text to write for the book. Nonetheless, I think it would make a wonderful book, so I plan to move forward.

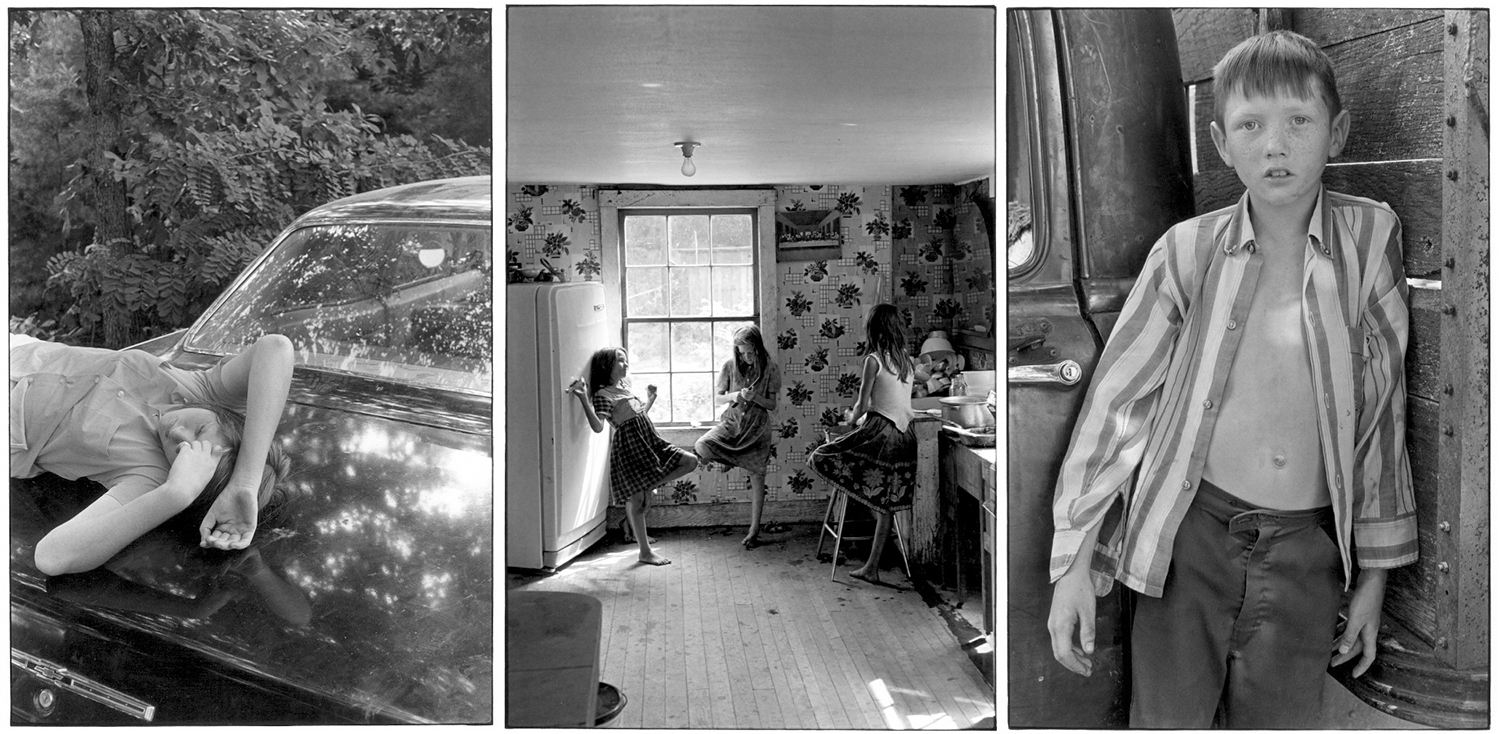

I had never seen a William Gedney photograph before beginning classwork at Duke’s Center for Documentary Studies. Gedney’s work is archived at Duke’s Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. One of our classes visited the archive and I was immediately taken with his photographs. What’s most striking to me about Gedney is that he went to eastern Kentucky at a time when most of the pictures being made there were being used to highlight and call attention to poverty. What’s more is that he only made two trips there in 1964 and 1972, spending a total of 29 days in Kentucky. Yet many believe, as do I, that this is some of the strongest work of his career. He quickly became a part of the Cornett family and worked amongst them with a meticulous, quiet familiarity shown in the photographs he made there.

In the early 1960’s, Appalachia saw a flood of photographers, news crews, and filmmakers (think Charles Kuralt’s Christmas in Appalachia circa 1964) come into the hills and hollers as part of the War on Poverty campaign. By and large, they formed a disparaging visual narrative of the place I was born and raised. Yet somehow, William Gedney transcended that tendency and instead made photographs of grace, beauty, and simple existence all the while capturing the real environs of his subjects. There must’ve been something about his spirit that caused him to see what others did not, would not, perhaps could not.

William Gedney died on June 23, 1989 at 56. In his lifetime, he was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship for photography (1966-67), a Fulbright Fellowship for photography in India (1969-71), a National Endowment for the Arts grant in photography (1975-76), and several other grants and fellowships. He had a show at the New York Museum of Modern Art (1968-69) as well as more than a dozen other exhibitions. What surprised me about this is that Gedney never published a book. Four years after his death, in 1993, Duke University became the repository for 51.3 linear feet of Gedney’s work. Margaret Sartor, a photographer, writer, and teacher at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke, was approached by the library and asked to put together an exhibit of Gedney’s work. In 2000, Sartor and Geoff Dyer coedited What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney, which quickly sold out and is now out of print.

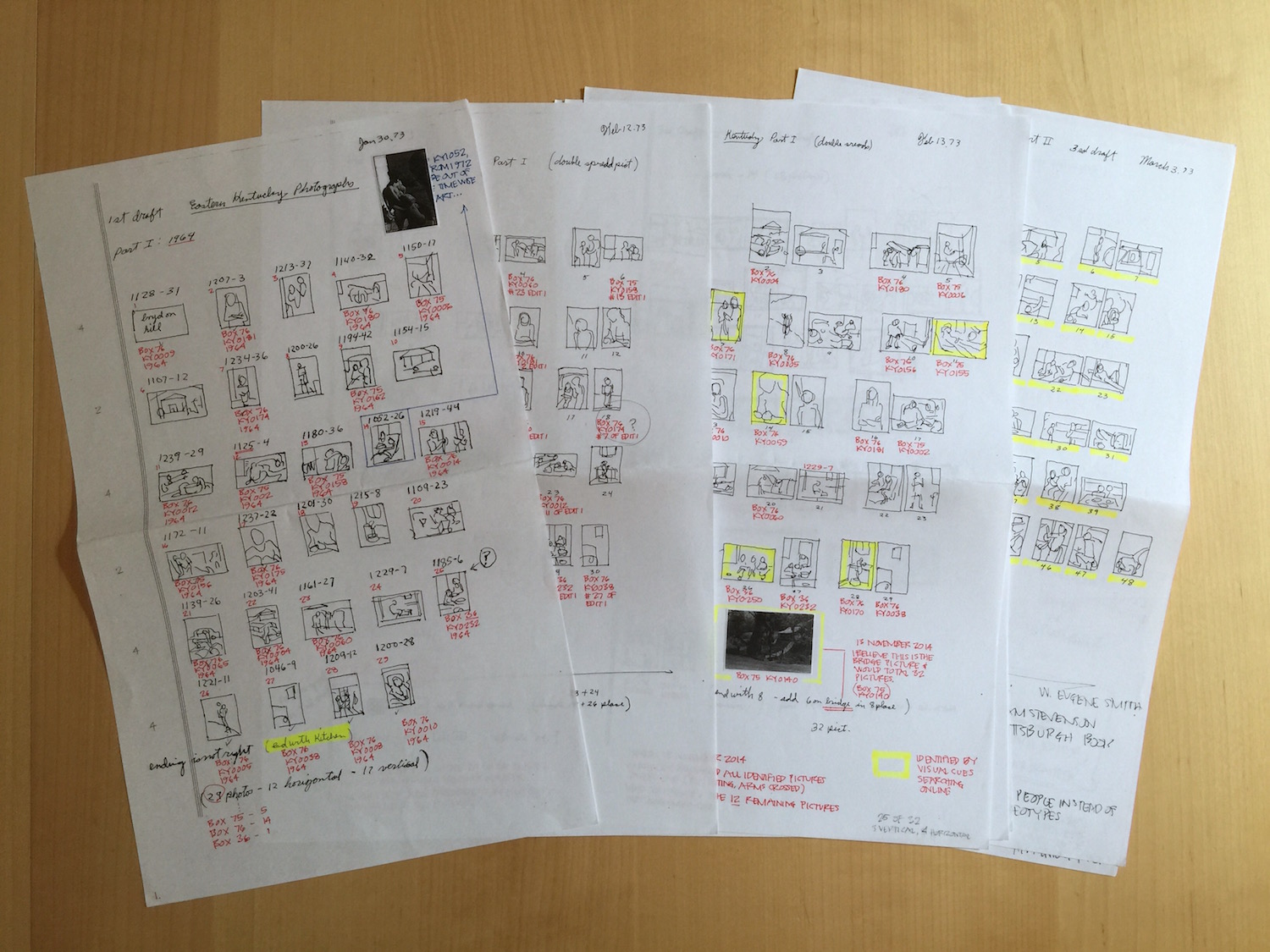

As years passed and my fascination with Gedney and his Kentucky photographs grew, I began spending time in the archive going through boxes and boxes of work prints, notebooks, and book dummies. It was here that I came across hand-sketched thumbnails (below) of an early draft for a book of his eastern Kentucky photographs. There were several pages of sketches, several of which listed the corresponding negative and contact sheet number, and it became clear that this was a book he wanted to make. He split the book into two parts – 1964 and 1972 – and included 80 photographs. Thanks to his notes, I was able to identify and locate 73 of the 80 pictures in the archive at Duke. The entire Gedney collection is currently being re-digitized and I hope to be able to identify the remaining seven pictures later this year. Including some of these sketches in the book will be a fascinating addition.

While working on this, I ordered and sequenced the images according to Gedney’s sketches and notes and created a couple of 11" x 17" contact sheets to study and understand his process a bit better. I also created a mock cover and used it to wrap my copy of Andre Kertesz: Paris, Autumn 1963, which incidentally is very similar in makeup with how I’d like to design the Kentucky book. It measures roughly 7.5" x 9.5", 80 pages, and was published by Flammarion in 2013.

I've consulted with Margaret Sartor, who was kind enough to invite me over to dinner earlier this year and along with her husband, Alex Harris, helped me think through some of the processes needed to make this book come to life. She has been instrumental in my learning about Gedney’s work. Lisa McCarty, curator of the Archives of Documentary Arts at Duke, has been incredibly supportive of this project and seeing it come to fruition.

So, if you’re a publisher, love the work of William Gedney, and want to see this book made, please drop me a line. I’d love to talk with you.

All three vertical photographs – William Gedney Collection, Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. All other photographs and content - ©2015 Roger May