It usually doesn’t take me six months to share my thoughts about a photobook, but nevertheless here we are. When I saw the first spreads of Sheron Rupp’s book earlier this year, I reached out to Kehrer Verlag’s public relations folks and asked for a review copy. The book arrived in early June and I knew before I reached the end it would be one of my favorite photobooks, and one of the most beautifully designed and printed books I’ve seen. That part didn’t take six months.

In July, my daughter was to give birth to her first child a few states away, so I stacked Rupp’s book in a neat pile of other work I planned to get to and prepared to become a grandfather. I looked at the book often, familiarizing myself with its pictures, the organization of the work, and the feelings – all the feelings – the book generated for me.

My granddaughter, Waylon Jane, lived for 24 days. In early August, my family and I found ourselves grieving in ways we never thought possible. On the surface, I tried to maintain some sense of normalcy, but inside, spiritually, emotionally, creatively, I was coming apart at the seams. I carried Rupp’s book back and forth to work, thinking I’d write about it at some point, needing to write about it at some point. It moved from my backpack back to my desk and then to the bookcase by our front door. Every time I walked by it, I was reminded that I wasn’t ready to write about it yet. And a couple of days ago, I picked it up, looked through it again and decided it was time.

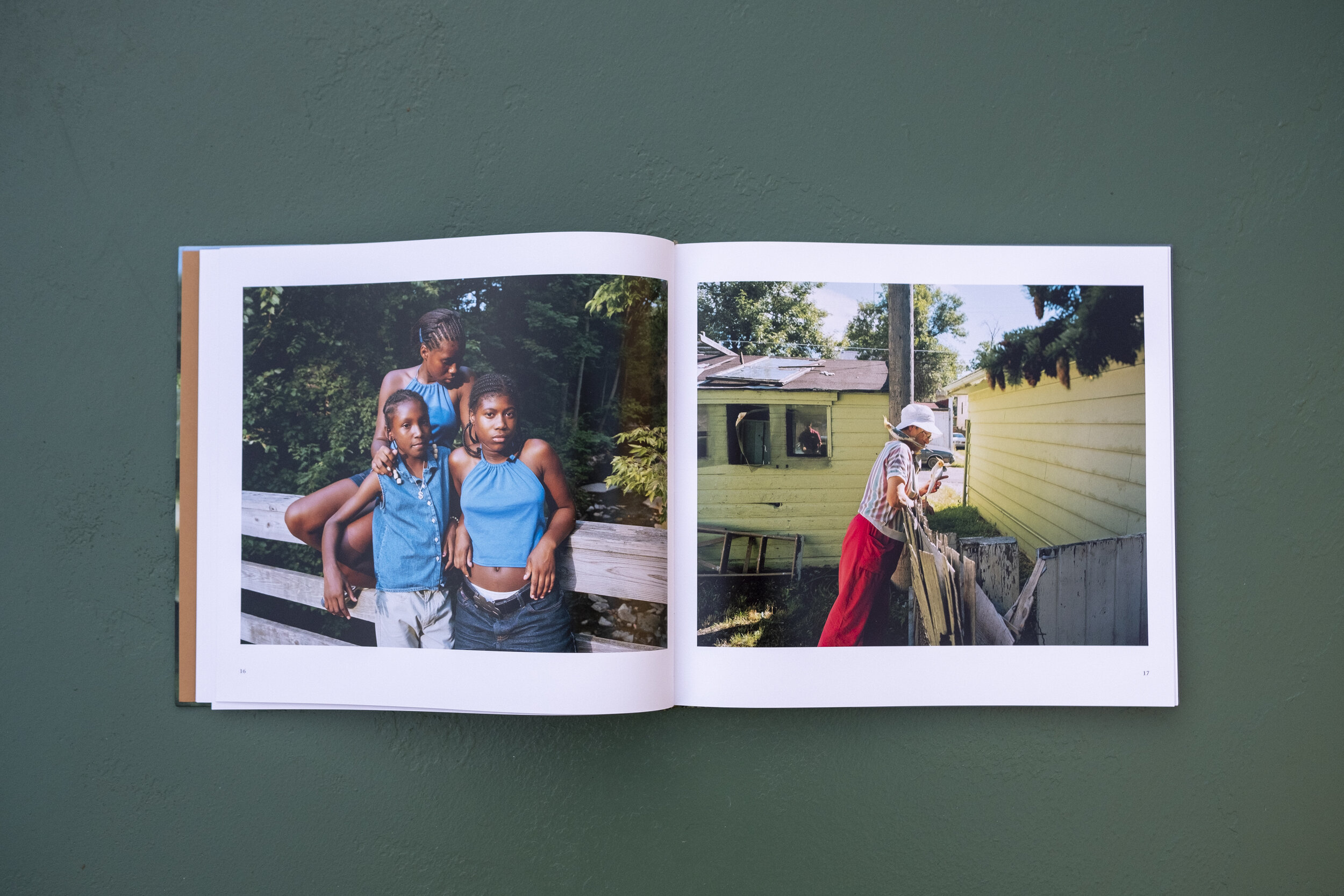

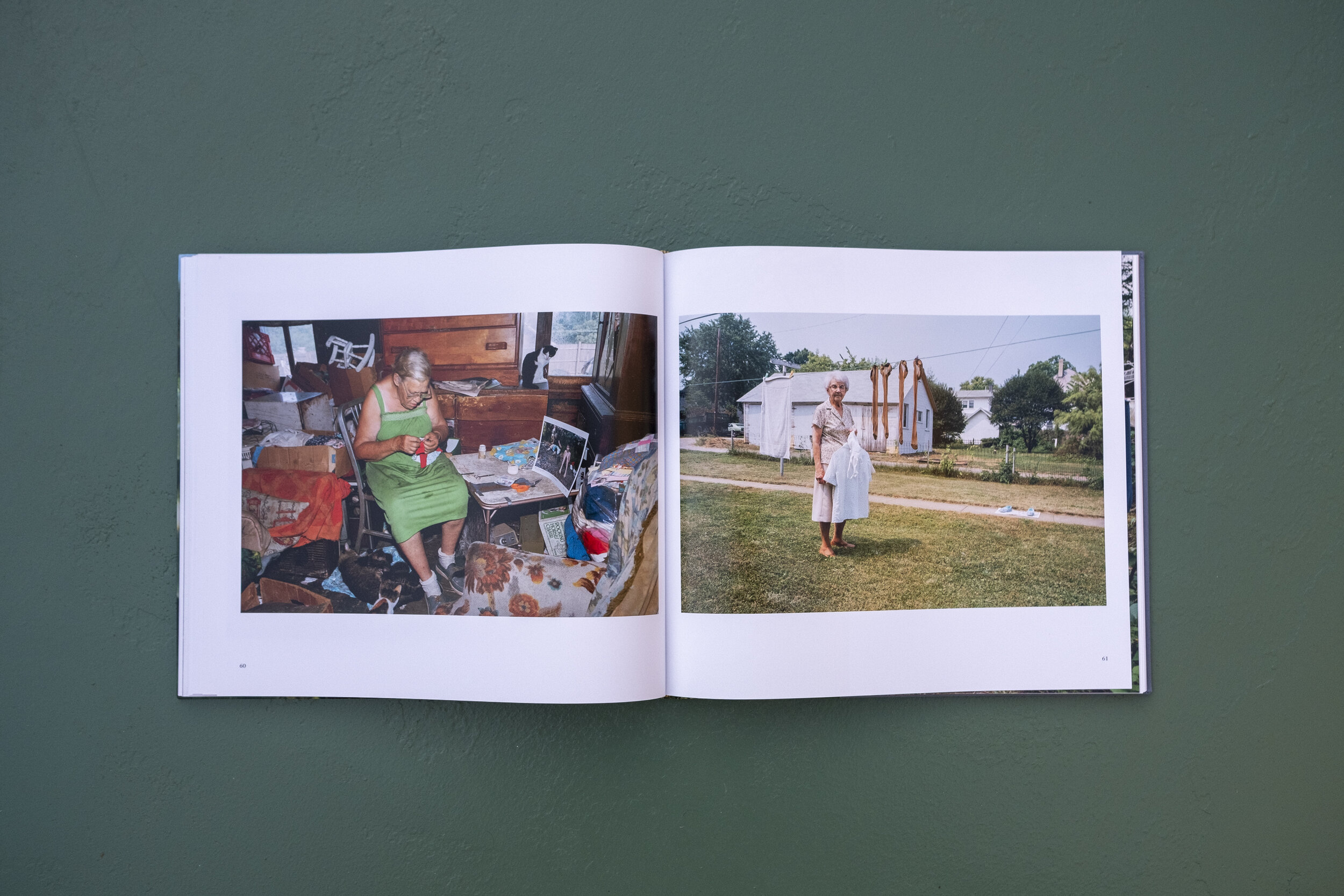

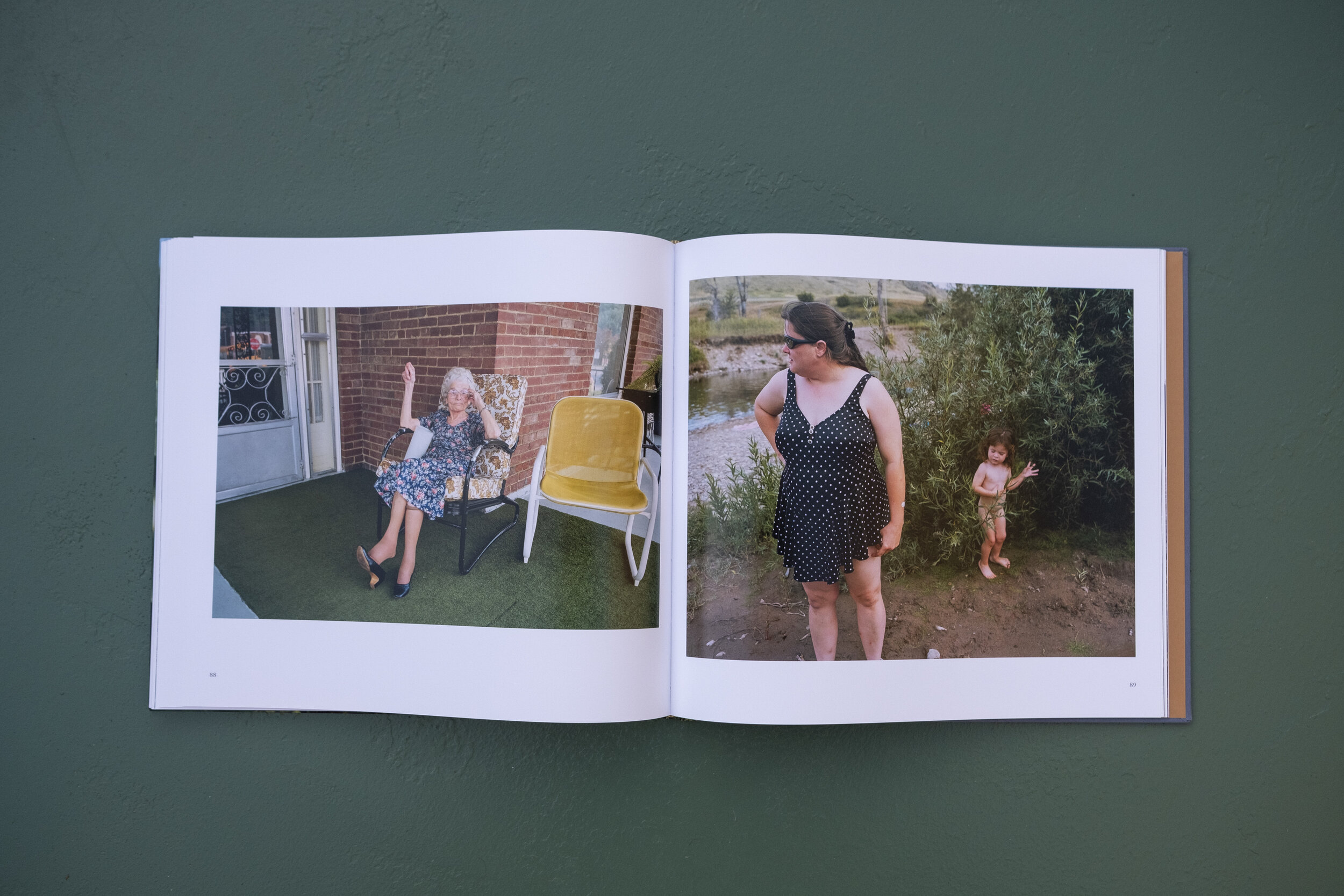

One of the great gifts that books like Taken From Memory gives us is the opportunity to connect to something so beautiful, so tangible, and to be able to hold in our hands moments of inexplicable wonder and refined curiosity. It has the familiarity of a family photo album without a snapshot aesthetic. So much attention to detail is given that it’s hard to imagine making a handful of pictures like these much less the 75 included in the book. It is in every sense of the word, astounding.

The book’s design is wonderful in its own right. Measuring 12” x 11”, it ranks as one of my favorite photobook dimensions; not unwieldy or unmanageable, but large enough to appreciate the meticulous compositions, colors, and shadows Rupp’s work offers. All the details seem to be dialed in just so, a testament to designer Anja Aronska of Kehrer Design. As an object, the book is quite remarkably made and presented.

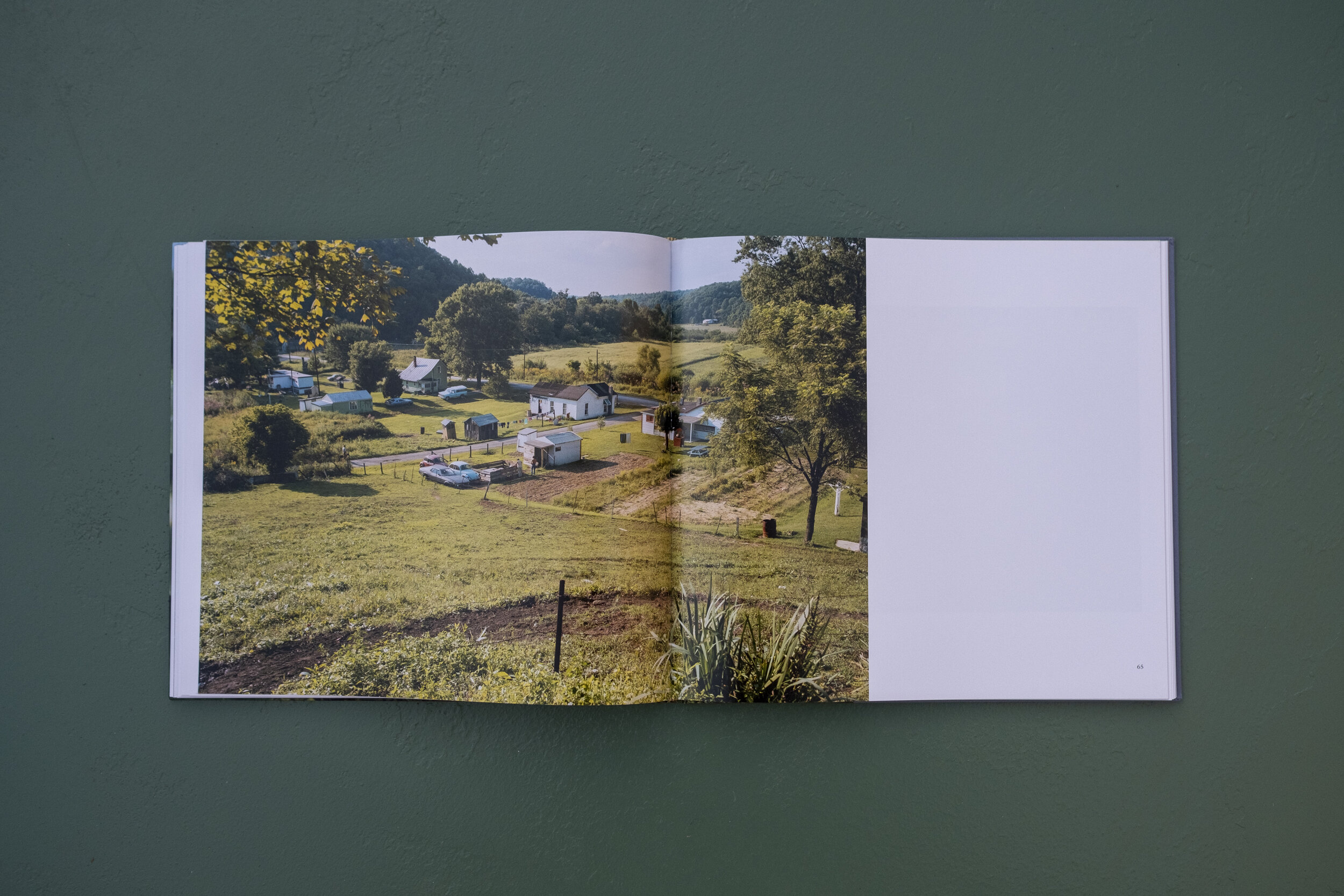

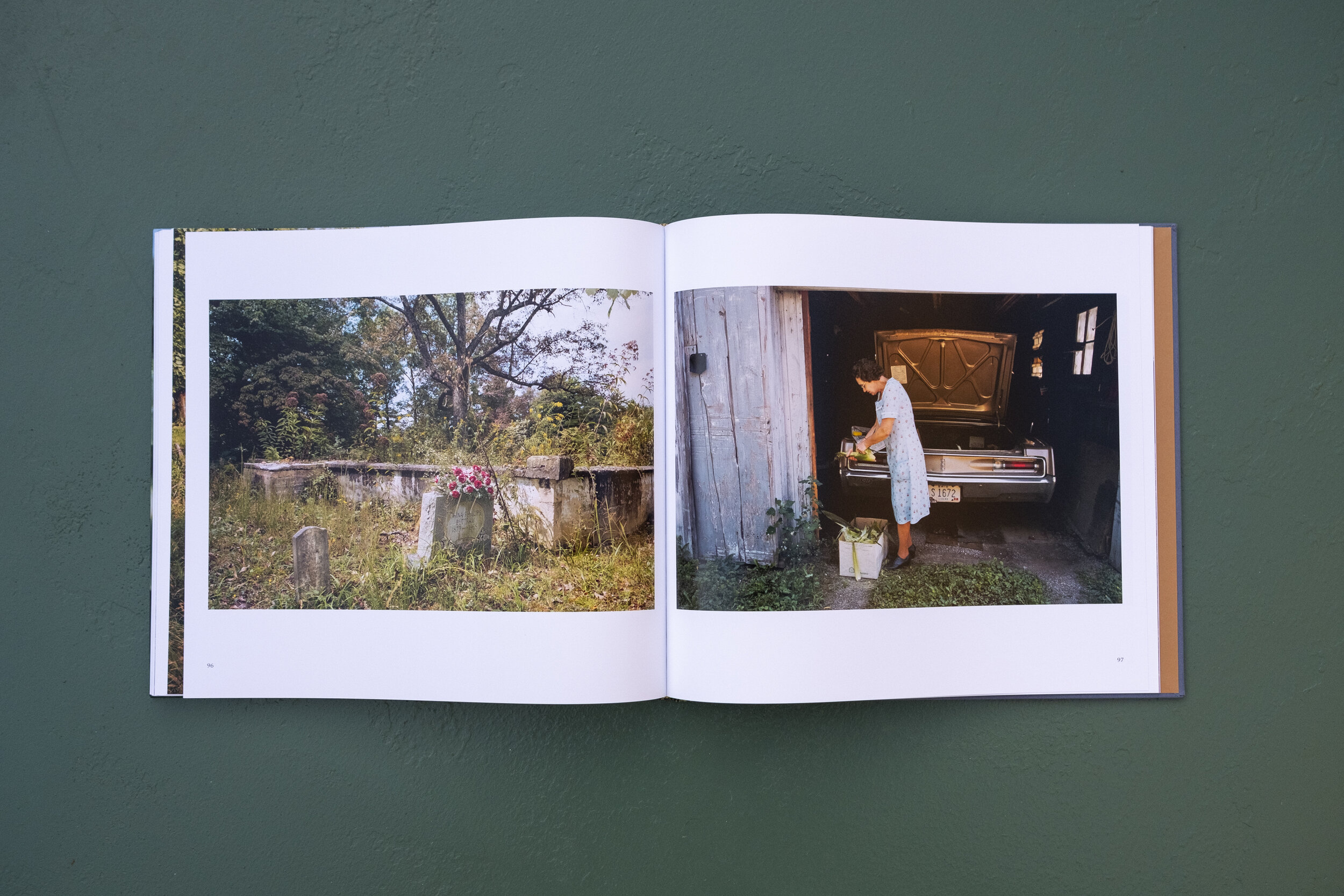

Taken From Memory feels like a body of work that could’ve been made exclusively in Appalachia, yet only 18 photographs were made in what the Appalachian Regional Commission regards as Appalachia. In addition to Kentucky, Ohio, and Tennessee, we see photographs from Vermont, Montana, Massachusetts, and several others states. So why does this feel so much like home to me when I’ve never even been to Montana? I’ve come to believe Taken From Memory holds the ability to transmit the feeling of intimacy and of seeing and being seen in a way that makes it more than just a photobook.

Every photograph contains, and ultimately reveals, something one could easily overlook at first glance, rewarding the viewer for looking a bit closer and staying a bit longer. As a photographer, I’ve often found that’s when the best pictures are made – when you stay a little longer and look a bit closer. As a viewer, I’m pleased to experience this in a book of photographs that offers no shortage of beautiful detail.

Rupp’s work implies a connection with the folks being photographed that I find rare in much of the work I see. Growing up, it was common to hear the phrase “never met a stranger” when someone was describing my grandfather, who could seemingly talk to just about anyone at any time just about anywhere. Rupp’s work suggest to me that she’s never met a stranger or at the very least, someone who stayed a stranger for very long. Perhaps that’s another facet of her work that makes Taken From Memory seem so much like home.

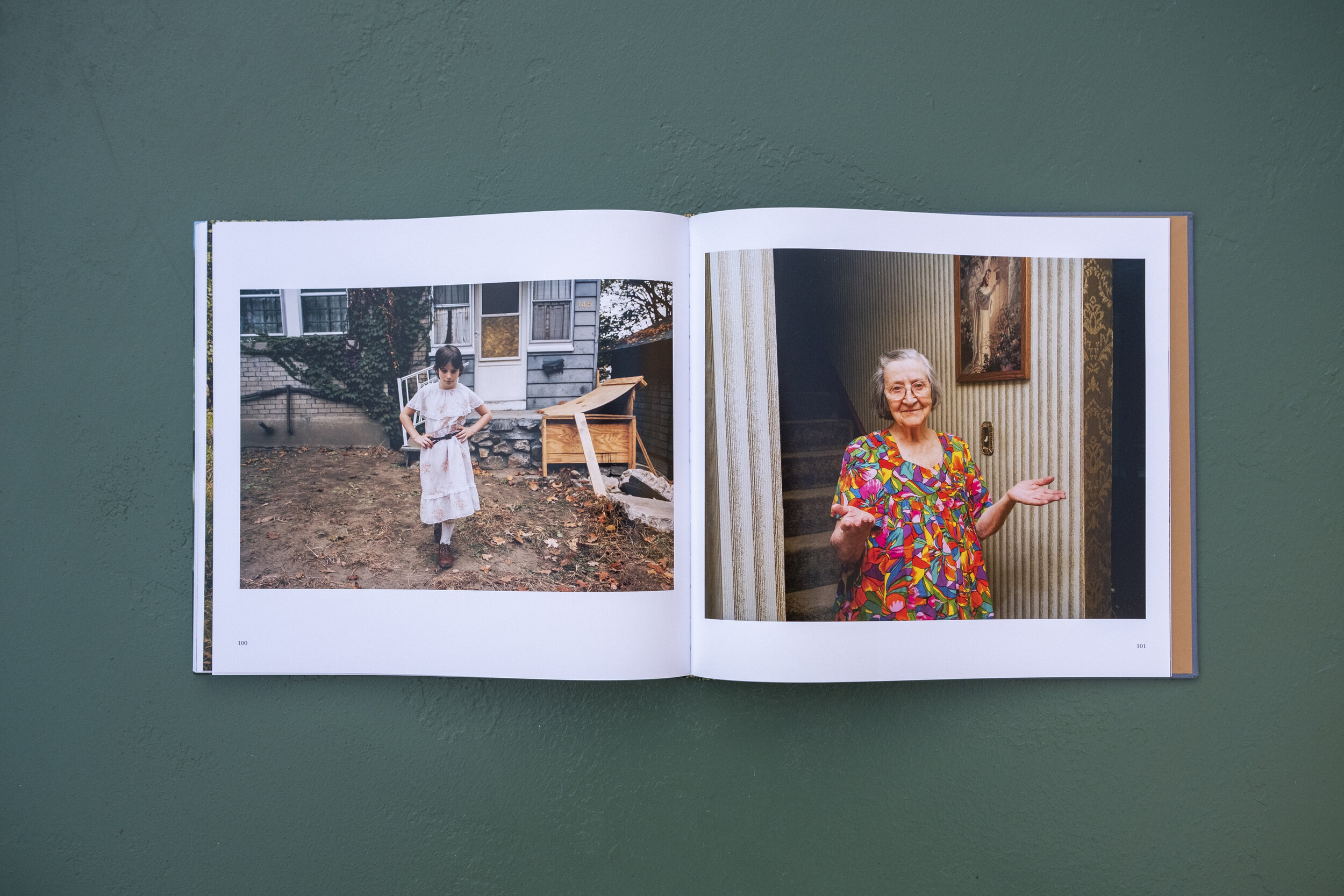

John Szarkowski (1925-2007), who served as the Museum of Modern Art’s director of the Department of Photography for nearly 30 years, said of one of Rupp’s pictures in 2006, “There’s a woman in the [Getty] show who I think is really good. [Looking through catalog.] Sheron Rupp. Don’t ask me why that’s such a good picture, it’s just a perfect picture.” (See below.) He continues, “The basic material of photographs is not intrinsically beautiful. It’s not like ivory or tapestry or bronze or oil on canvas. You’re not supposed to look at the thing, you’re supposed to look through it. It’s a window. And everything behind it has got to be organized as a space full of stuff, even if it’s only air.”

St. Albans, Vermont, 1991. © Sheron Rupp. “Don’t ask me why that’s such a good picture, it’s just a perfect picture.” John Szarkowski.

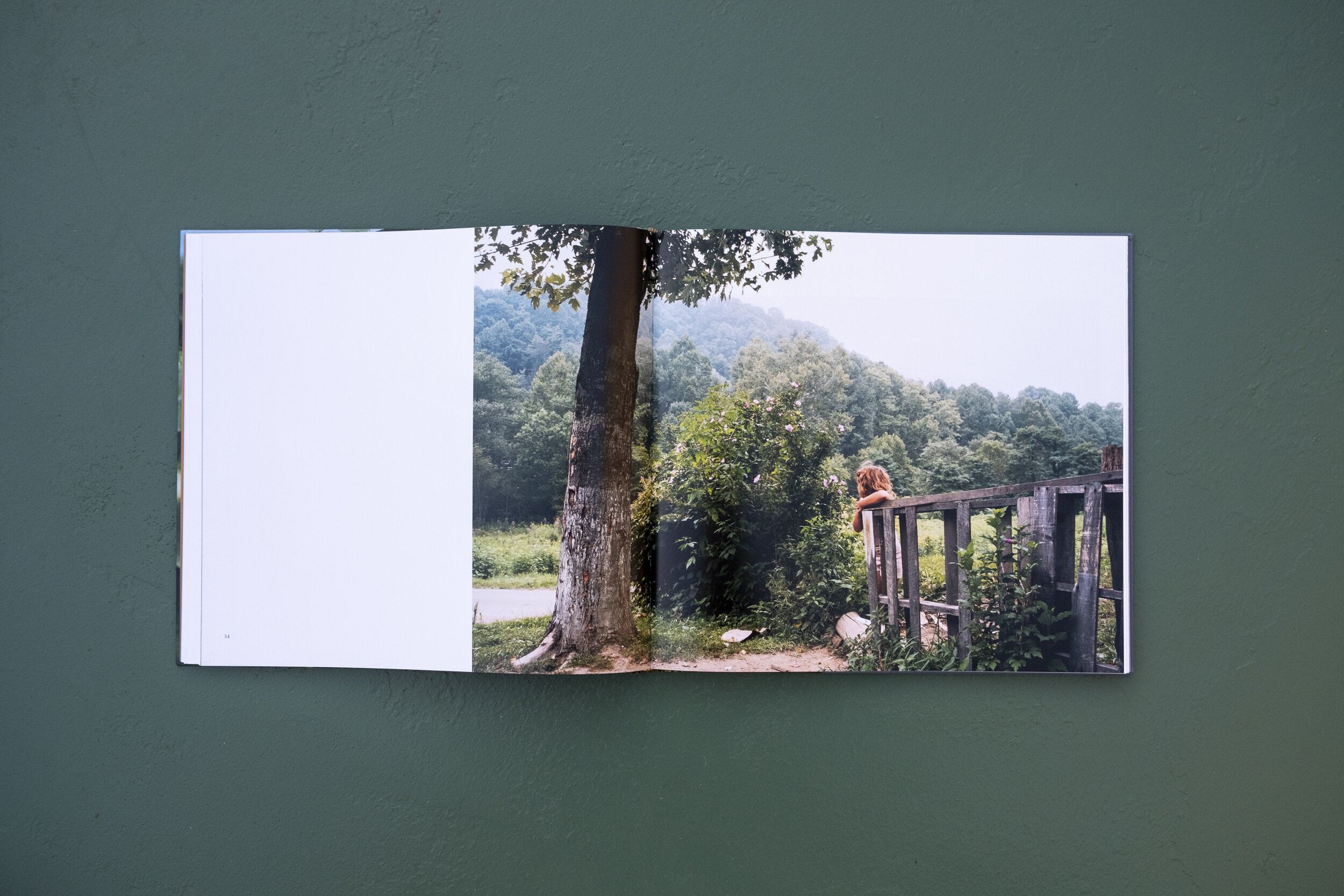

There is a perfect picture for me in this book. In it, a small girl leans against a wood fence. Her gaze is toward the hill across the way, beyond the Rose of Sharon bush much bigger than she is. Her hair is caught by a breeze coming through, which I imagine carries with it the fragrance of the Rose of Sharon I remember so well from my grandmother’s front yard. Maybe she’s playing hide and go seek and she’s counting. Maybe she sees something on the hill. I close my eyes and imagine Waylon Jane and the backyard lightning bugs of summer I’ll never see her chase and catch and let go again. I imagine her voice and her hair and her laugh in the hills she never got to see. And in my mind, it is a perfect picture, familiar and home.

Ironton, Ohio, 1985. © Sheron Rupp.

*Editorial note: I received a complimentary review copy of Taken From Memory from Kehrer Verlag.

Further reading:

LA Weekly Interview with John Szarkowsky

The New Yorker, Two and a Half Decades Observing Life in Rural America

The Heavy Collective, May 2019

Also of note, Susan Worsham’s interview with Sheron Rupp is featured in Ahorn Archive 1, which ships later this month - https://ahornbooks.com/product/ahorn-archive-1/