Last week, I published Shelby Lee Adams' essay "The Work of Looking," as a result of our phone and email conversations about his life and work in Appalachia. Part of our conversation was centered on the Appalachian stereotype and how we as viewers, both Appalachians and non, look at mountain people, culture, and place.

Last week, I published Shelby Lee Adams' essay "The Work of Looking," as a result of our phone and email conversations about his life and work in Appalachia. Part of our conversation was centered on the Appalachian stereotype and how we as viewers, both Appalachians and non, look at mountain people, culture, and place.

For years now, Shelby Lee Adams’ work has challenged me, both as an Appalachian and a photographer. I’d never been able to sit with his work very long as it almost always elicited a strong, visceral, and ultimately defensive response. Frustrated by the stark depiction of poverty and implied stereotypes of Appalachia and her people, I dismissed his work as the kind I didn’t want to make. And then we talked.

What started to surface for me during the course of our conversations were my own biases and the implied stereotypes I bring to the table when looking at photographs - especially photographs from Appalachia. I didn't want to deal with the hard work of looking at my own prejudices, so it was easier to dismiss the work as typical stereotyping of Appalachia. There is no real work involved in this way of thinking. It doesn't require anything of me. It's safe, but it isn't honest.

Several months ago, I contacted Candela Books founder Gordon Stettinius and asked for a copy of Adams’ latest book, Salt & Truth, to review here. Since the book was released nearly a year ago, I didn't expect they'd actually send one, but they did. I also didn't expect that spending time with the work would ask me to take an honest look at how, and why, I look at Shelby Lee Adams’ work the way I do. But when I sat with this beautifully edited, sequenced book, it did just that.

Salt & Truth is Adams’ first book with Candela and his fourth book overall: Appalachian Portraits (1993), Appalachian Legacy (1998), and Appalachian Lives (2003). Salt & Truth (2011) contains 80 plates in its 128 pages along with introductions by James Enyeart and Catherine Evans. Perhaps the most powerful feature of Salt & Truth, is Adams' own eleven-page commentary, "The Roots of Inspiration," wherein Adams writes:

"Many American ideals are dedicated to sleek, fashionable, and powerful images of ourselves. When presented instead with a more complete picture of someone who looks dissimilar, some will balk and accuse the presenter of the descent of the people and community. We have oppressed tenuous people for centuries by hiding them in the shadows...People's faces reflect what God has given them but also reveal what others have inflicted, shunned, or propagated."

Adams' work has become so iconic that it’s nearly impossible to have a serious discussion about Appalachian photography without including him. His work has been widely praised - and criticized - by a number of people, yet it has continued, strong and steady for nearly 40 years. There's something to be said for anyone - photographer, historian, or preacher - that continues to go back to the same communities year after year, earning and keeping the trust and friendship of the people. You can't continue to make this kind of work and have these types of familial connections if the people you're photographing feel taken advantage of.

“I love his work. I've had so many conversations about this, and I've had some people seriously attack me for liking his work. I deliver the mail 110 miles through these mountains, so I go up hollers and see places that a lot of people who have lived here their entire lives have never seen. I know several of the people in Shelby's books. I know family members of them too. I feel very deeply about his photos and I see the beauty and I think it's important for people to see. This is a whole culture of people that are rarely seen and often ignored. They're the folks being destroyed by mountaintop removal (mining). They're the folks that are shunned when they go into town. They deserve to be seen, and he's the only person documenting that culture (that I know of). And I have to say that the people in Shelby's books are not a minority, at least not here. I've noticed at times that it is difficult for people to see the whole picture. Look at the photo on the cover of the book. I see a guy that looks like so many other guys around here: no shirt, tattoos, sunglasses for riding his 4-wheeler. I've seen arguments where people thought Shelby should have made him put a shirt on. How silly! He was hanging out shirtless, he got photographed shirtless. But mostly what I see in that photo is that amazing time of day when the sun is hitting the mountains just right and lights up one part of it so that it can take your breath away. Shelby captured that. He saw that. I've seen people call his pictures disgusting, and I can't fathom how someone could say that about another person. These are human beings and if we look at the photos and see something disgusting, then I believe that is a problem inside of ourselves, and not the problem of the photographer or the subject.” - Cindy Shepherd, Oneida, Kentucky

Jöerg Colberg over at Conscientious, in his piece “Photography and Place: Appalachia” writes:

“I believe the best and possibly only way to deal with the problem of representation is to embrace the bias. So let’s not call it bias, let’s call it what it really is: The artist’s creative vision, which is coupled with the artist’s personal integrity. That’s what it comes down to. I believe the best way to present a body of work about a place is to say: This is what this place looked like to me. I’m not showing you the place, I’m showing you my view of it. Now deal with it!”

Colberg continues:

“I personally believe that as much as any artist can do whatever they want, they still have the personal responsibility to understand and navigate the context their work lives in. However highly you regard yourself as an artist, you work does not exist in a vacuum. It is being placed into at least the history of photography (around 170+ years), and it also is being placed into our culture, that odd, malleable thing that keeps shifting and moving.”

Adams', in his own words, puts his work in context in Salt & Truth:

"It is the spirit of the mountaineer living in the hollers that motivates and interests me. The visual representation of this culture has rarely been made from inside. I don't deny, nor do I see, poverty as a focus in my work; once the "poverty" filter is removed, a different world emerges. The culture is multilayered in expressing the fullness of life. Mountain people are more accepting of diverse representations of themselves than the viewer might imagine because they know themselves and are spiritually sel-assured."

From Estelle Jussim's, Propaganda and Persuasion:

“Educators may prate about photographic literacy, but what is needed is an understanding of how any picture could miraculously transform painful information into coherent social action. For the obvious truth is that a single photograph, unaccompanied by verbal messages, cannot simultaneously contain both the image of the problem and the solution to the problem. A photograph, therefore, would seem to be able to pose the question, to imply a situation for which some other medium might be needed to provide the answer.”

So what are our expectations of Appalachian photographs? How willing are we to be self-aware when looking at this kind of work? Any kind of work? What are our own biases? We can’t oversimplify Shelby Lee Adams’ photographs because it requires thought and honesty. Truly there is work involved in looking at these photographs and though some of his work isn't always easy to look at, I'm grateful that Shelby Lee Adams' work asks me to put my hand to the plow.

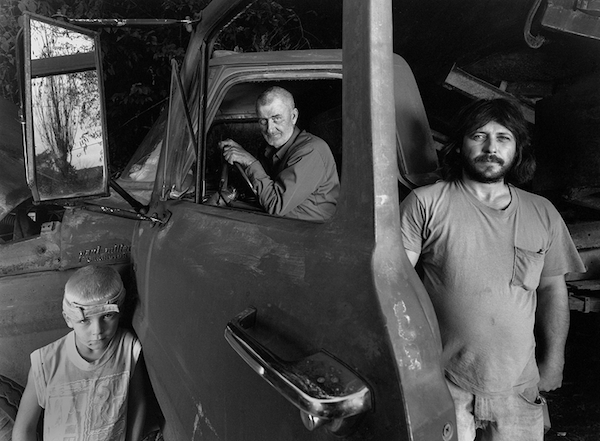

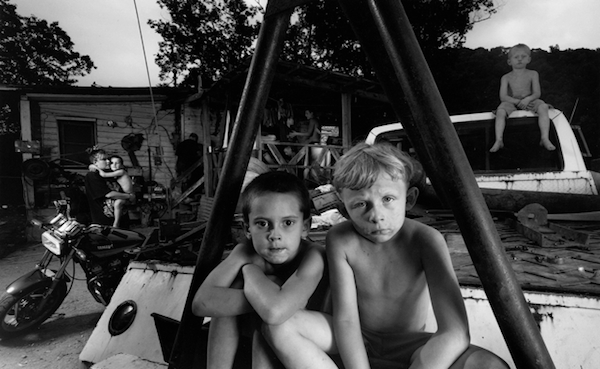

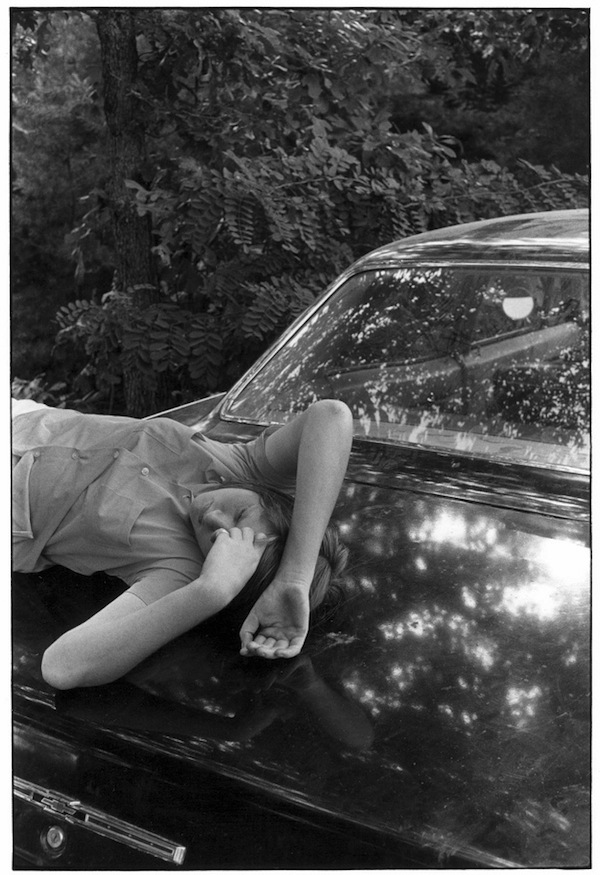

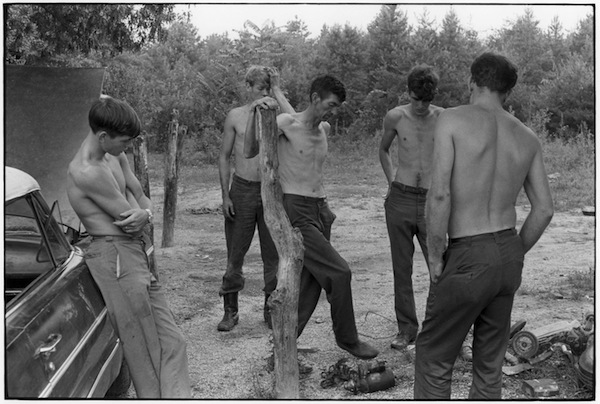

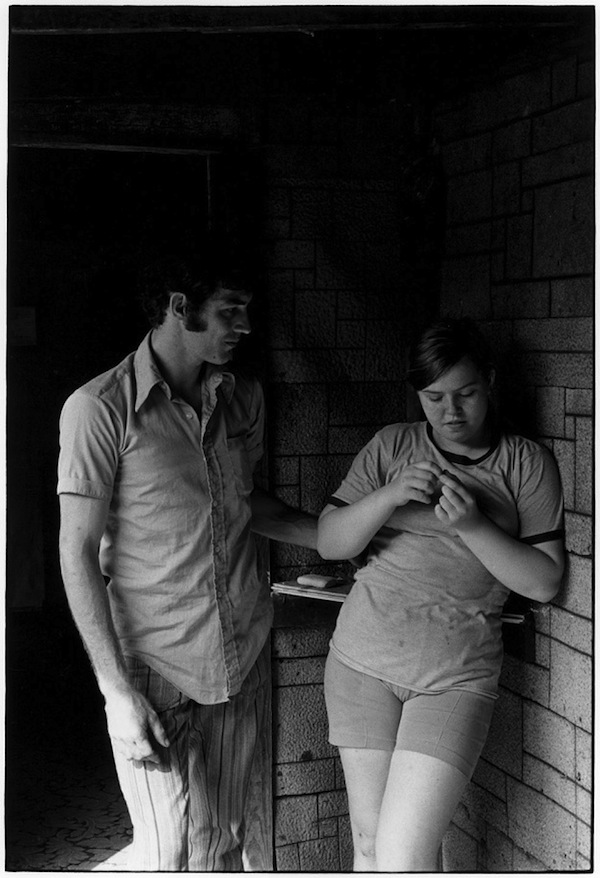

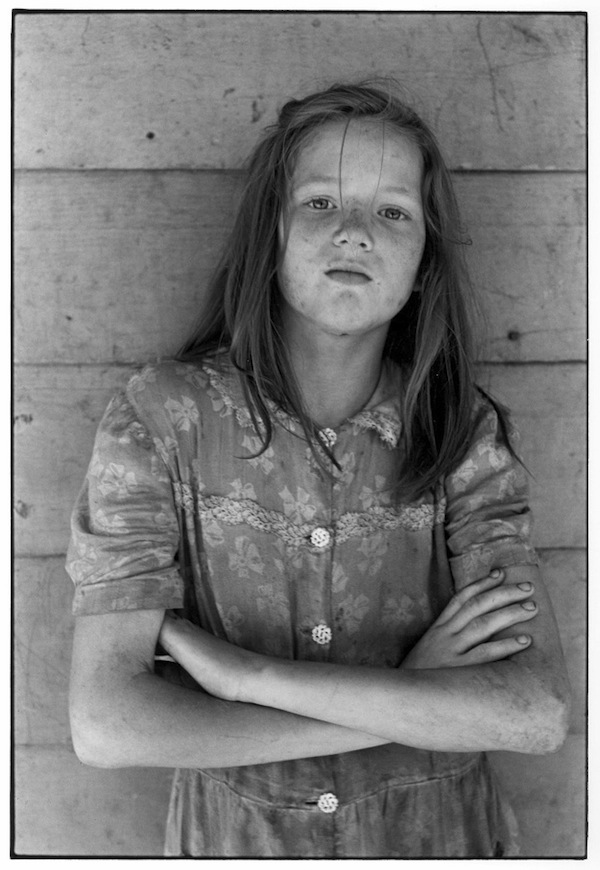

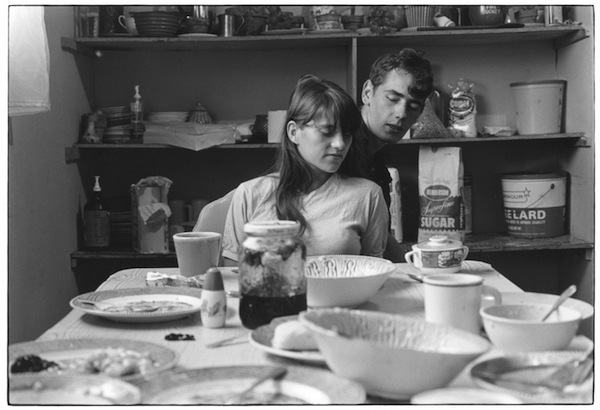

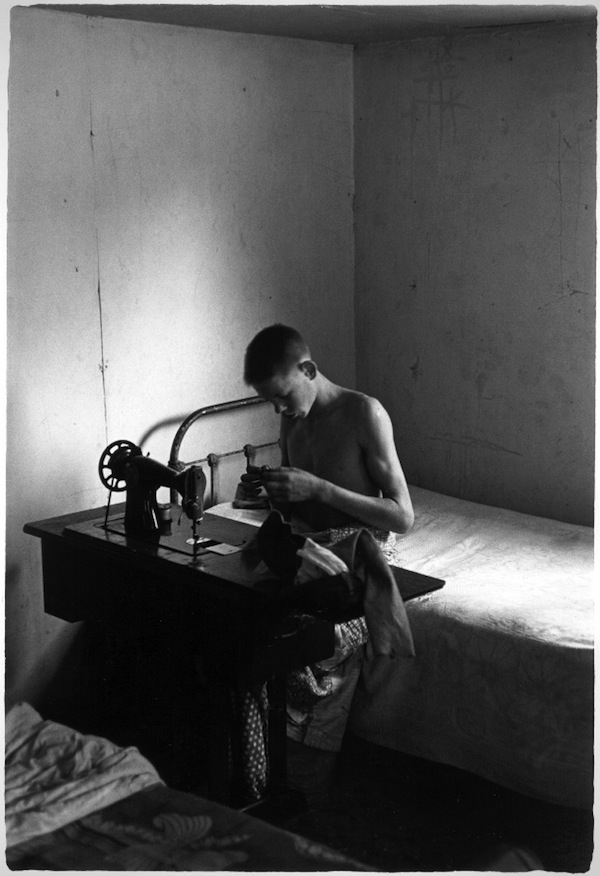

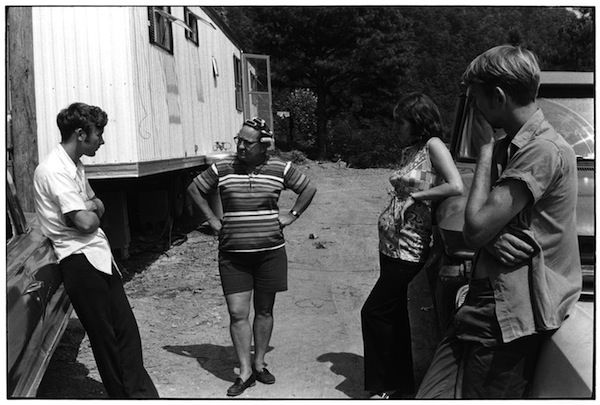

Seven black and white photographs from Salt & Truth © Shelby Lee Adams. 1. Eagle's Nest, 2008. 2. Lloyd Dean with Family and Coal Truck, 2002. 3. Dan, Krissy and Leddie, 1993. 4. Robbie and Tyler on Wrecker, 2003. 5. Melony, 1996. 6. Alma Gail and Boys, 2003. 7. Brother Ish, 1994.