CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WINNER – CAROLYN PARKER!

CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WINNER – CAROLYN PARKER!

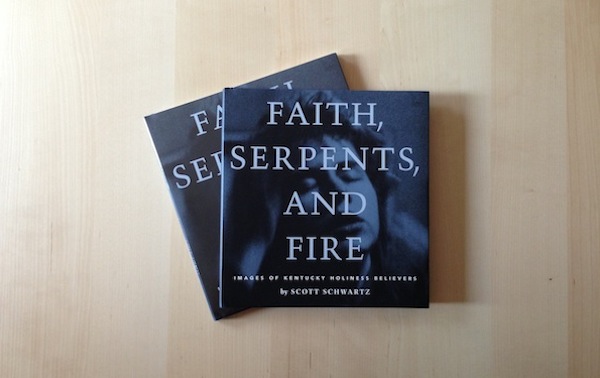

Hardcover| 9.5 x 9 inches | 128 pages | 88 black and white photographs University Press of Mississippi, 1999 | Scott Schwartz

"And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." Mark 16:17-18, King James Version

As far back as I can remember, well before picking up a camera, I've been fascinated by the serpent-handling faith. This religious tradition has long been ridiculed and used as an example to highlight the Appalachian backwoods stereotype. I've wanted to photograph these services for a while now and though I'm far from the religious upbringing of my Appalachian childhood, I look forward to making some pictures later this summer. Why? I'm simply fascinated by an obedience that would call one to take up a serpent as an act of worship. I'd like to photograph these services as a celebration of faith and tradition.

I picked this book up at the 2013 Appalachian Studies Conference in Boone, North Carolina. At the same time, I was reading Dennis Covington's fabulous 1995 book Salvation on Sand Mountain: Snake Handling and Redemption in Southern Appalachia (which Schwartz lists in his bibliography). One of the more striking passages from Convington's book is below, and as a photographer, I've mentally substituted 'photographer' for 'writer' and found it to be especially true:

"I believe that the writer has another eye, not a literal eye, but an eye on the inside of his head. It is the eye with which he sees the imaginary, three-dimensional world where the story he is writing takes place. But is also the eye with which the writer beholds the connectedness of things, of past, present, and future. The writer's literal eyes are like vestigial organs, useless except to record physical details. The only eye worth talking about is the eye in the middle of the writer's head, the one that casts its pale, sorrowful light backward over the past and forward into the future, taking everything in at once, the whole story, from beginning to end."

Before I continue, I should let you know that if you're expecting technically superb, sharp images from Schwartz's book, you'll be sorely disappointed. What the book lacks in technical merit, it more than makes up for with the supplemental text and depth of the work in its entirety.

Schwartz notes in the introduction:

"The photographs were taken with 35mm, 400 ASA film, without flash, in an effort to intrude as little as possible upon the services. As a result, the film was "push-processed" two and three stops. The pronounced grain and the strient patterns of light in these images are the result of this process and of my desire to have the photographs represent the mood of the spiritual experiences. The photographs and essays record the complex and sometimes humorous social interactions that I encountered and provide an intimate glimpse into serpent-handling practices and beliefs, moving beyond the stereotypes of Appalachian snake charmers and fire eaters to illustrate the deeply personal and communal spirituality that is an integral element of the services."

It's clear to me that though Schwartz took a scholarly approach to the fieldwork conducted for this book, much like Covington's journalistic approach to Salvation on Sand Mountain, both men experienced far more than they bargained for. I don't think it was an accident that I discovered these two books at roughly the same time I'm doing prep work for my own experience with this community. Together, these books have helped reinforce my interest in the subject and my desire to add another voice to the conversation.

Schwartz writes, "Everything seems so natural, yet the media's blitz about a recent serpent-handling fatality paints a much darker and more sinister picture of these people. However, I am drawn by a brighter image." It's usually then, and only then, that the media's attention is on this tradition. It's important to note that this isn't a widespread Appalachian religious tradition contrary to popular belief. However, when there's a fatality, such as Mack Wolford's in West Virginia last year, the notion that serpent handling is a common part of worship in rural churches throughout Appalachia is once again perpetuated.

Another passage from Salvation on Sand Mountain:

"It's not true that you become used to the noise and confusion of a snake-handling Holiness service. On the contrary, you become enmeshed in it. It is theater at its most intricate - improvisational, spiritual jazz. The more you experience it, the more attentive you are to the shifts in the surface and the dark shoals underneath. For every outward sign, there is a spiritual equivalent. When somebody falls to his knees, a specific problem presents itself, and the others know exactly what to do, whether it's oil for a healing, or a prayer cloth thrown over the shoulders, or a devil that needs to be cast out."

If you'd like a chance to win a copy of Faith, Serpents, and Fire: Images of Kentucky Holiness Believers, please leave your name, city, and state in the comments field by midnight EST, Friday, 26 April 2013. I'll select a winner at random the following day.

Hey folks! I'm excited to announce the launch of my

Hey folks! I'm excited to announce the launch of my  My friend Cindy Shepherd from Oneida, Kentucky posted a poem on Facebook a few days ago, which was an exercise she planned to do with a group of elementary school children. After reading it, I was moved and inspired to write my own version of 'Where I'm From.'

My friend Cindy Shepherd from Oneida, Kentucky posted a poem on Facebook a few days ago, which was an exercise she planned to do with a group of elementary school children. After reading it, I was moved and inspired to write my own version of 'Where I'm From.'