I had the great pleasure of spending several hours with Appalachian photographer Rob Amberg on a Sunday afternoon on the porch at Duke's Center for Documentary Studies. We visited for hours, talking about family, children, Appalachia, and photography among other things.

I had the great pleasure of spending several hours with Appalachian photographer Rob Amberg on a Sunday afternoon on the porch at Duke's Center for Documentary Studies. We visited for hours, talking about family, children, Appalachia, and photography among other things.

I asked Rob to write an essay to accompany some of his photographs for part one of this series, which focuses on more of his published book work. In the second part, I'll be sharing some of Rob's work from a more recent project. I'll also be announcing a chance to win a signed copy of his first book, Sodom Laurel Album.

Rob Amberg is the recipient of awards from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the North Carolina Humanities Council, the Center for Documentary Studies, and others. In 2004, he had the honor of presenting Sodom Laurel Album at the Library of Congress.

Looking for Place

I believe that finding one’s place in the world is an individual’s most challenging question. Where is that spot that best allows us to pursue our dreams and, at the same time, to address our responsibilities? Where is that place that makes us feel happy, at ease, challenged, productive, ourselves? For some of us that locus is no further than our own backyards. For others of us, finding our place takes groveling and searching before we come to where it just feels right. I have always fallen in with the groveling and searching crowd.

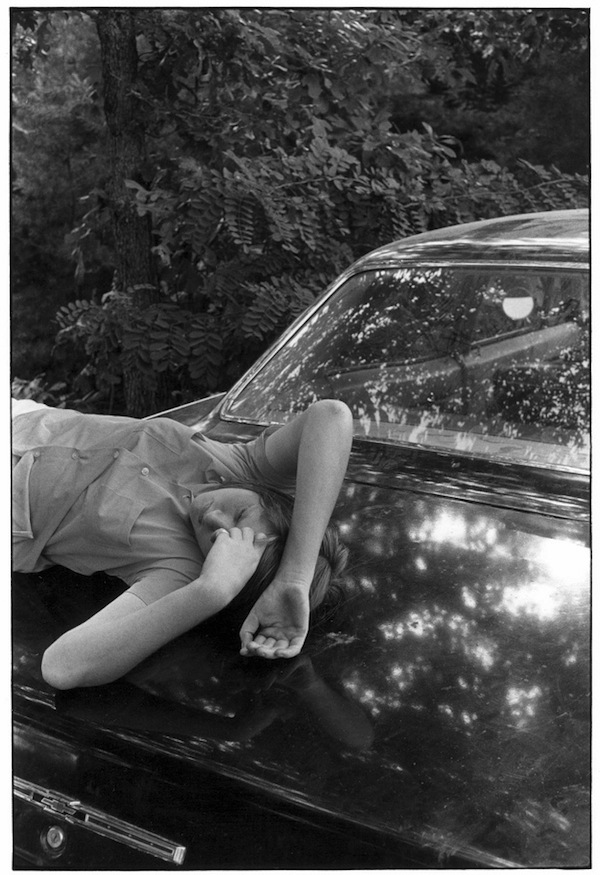

Photography is like that, too. On an immediate level, deciding where to stand and point the camera is the most basic of decisions a photographer makes. But before even that, because of photography’s dependence on an external reality, a photographer must decide where he is going to make his art. On what and who is he going to focus his attention? And what is he going to say?

Because I “ain’t from around here,” learning to maneuver through the intricacies and multiple layers of mountain culture involved a steep learning curve that I am still regularly reminded of, even after living here for almost forty years. It’s that depth of culture, and the power of the mountains themselves, that continues to spark my curiosity and keep me in place. True places, after all, are hard to find.

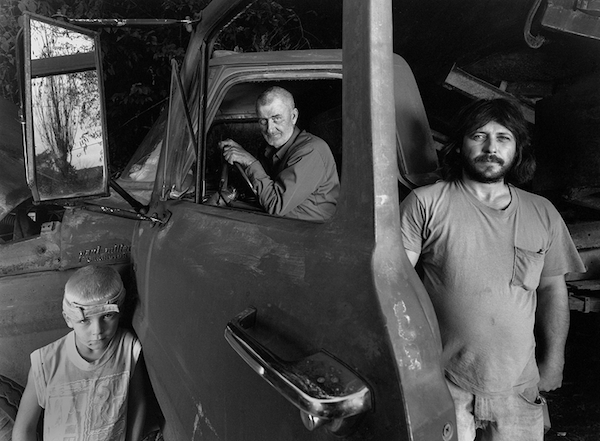

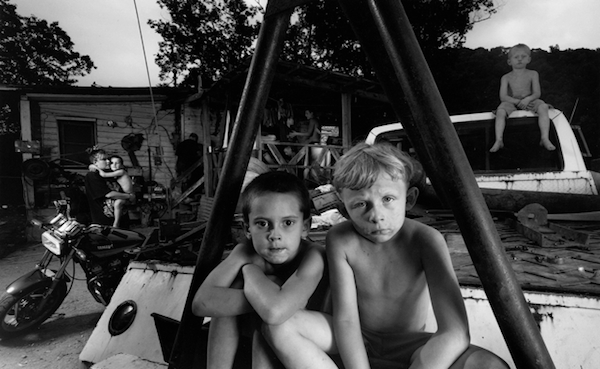

I have long considered myself a participant/observer. My desire to live in and fully experience the mountains and their people has matched my need to photograph them. Working with neighbors in their tobacco barns and tomato fields, attending their funerals and wakes, and playing a role in community functions not only serves to inform my photography, but more importantly, they link me to this place in an active way that goes far beyond simply observing. Firewood, spring water, gardens, animals, and farm maintenance are not only necessities that must be attended to, but also provide tangible evidence of work done when compared to the superficial nature of images on paper or computer screen, or theories discussed in the classroom.

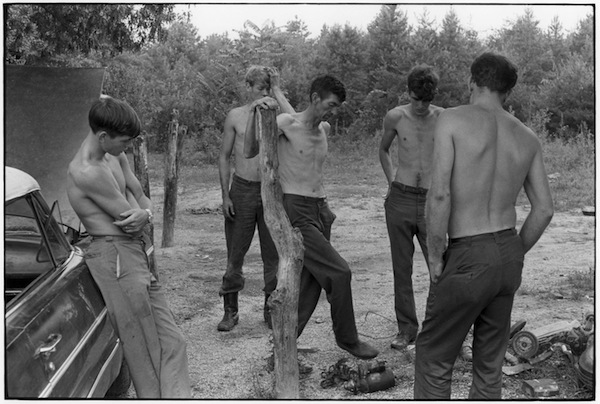

It was images that first brought me to the mountains. Like many boys of my generation I was fascinated by the lives of people like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone, especially as Walt Disney rendered them – heroic, brave, and romantic as they walked into those misty mountain sunsets. So, in 1973, when I followed an uncle’s suggestion to move to Madison County, as he had a couple of years earlier, those stereotypes were what I brought with me and what I looked for when I arrived. And those real world stereotypes – the wrinkled faces, wizened mountaineers, and old women in doorways – were easy to find in Madison County and I photographed many of them.

Over time, I began to realize how much about this place I was failing to see, or choosing not to acknowledge. While I was honed in on the romance of the place, the other side of the Appalachian stereotype – the clannishness, violence, poverty, and abuse – was also on display. While land is one of the primary values of mountain life, there was often a blatant disregard for the land itself evidenced by straight-piping into creeks, trash piles on the sides of roads, and serious erosion from clear cuts and overuse of chemicals. The county was nicknamed Bloody Madison for a notorious Civil War massacre of thirteen men and boys accused of being “Unionists,” but the moniker had been punctuated over the years by acts of random and personal violence. The year before my arrival, a young, female VISTA worker had been brutally murdered in a remote section of the county.

I also began to see and understand other dynamics at play in Madison. There were hundreds of new people - retirees, young professionals, artists, Latino immigrants, and back-to-the-landers - moving into the county, buying land, and making commitments to place. Concurrently, many of their local counterparts were moving out and off the land, wanting to be closer to the mainstream. For me as an observer, it became important to understand and document the county as a whole, as an evolving community, inclusive of a diversity of people and ideas, rather than one fixed in time.

Photography is about memory. Its unrivaled ability to capture detail offers the ability to recall the textures and feelings of the world around us at specific moments in time. For me, believability becomes an ongoing concern – a need to know that how I represent a subject speaks to the truth and can be understood as such by viewers. That is not to say that photographs are not ambivalent – they are – and the photographer, when presenting an image of place, is always at the mercy of the viewer’s experience, prejudices, and interpretation of an image. While it may be true that a picture never lies; it is equally true that a picture is worth a thousand words – words that often contradict each other in their meaning.

There was a week a couple of years ago when I was twice reminded of my “otherness” by people on radically different ends of the cultural, social, and economic spectrums. I had given an address at a conference, showing my work, and talking about changes in my mountain community. After the presentation, I was talking with a conference participant who accused me of fostering stereotypes and being “so Florida” in my thinking about Appalachia. This was ostensibly because I choose to embrace stereotypes in some of my images, rather than ignore them and because, in a general way, I thought the migration of new people into our community was a good thing, and that many of these people were “bright” and smart and brought new ideas and values into the community.

I mulled about his criticism in the following days, indulging my sensitivity to suggestions of misrepresentation in my work. It was summer and a couple of days later I was walking with my dogs on the road below our house, one of the few remaining dirt roads in the county.

I heard a truck coming up behind me and glanced back to see our community thug who had recently been released from jail. As he came alongside of me, slowing to keep pace with my gait, he looked over my clothing – shorts, tee shirt, white socks and sneakers – and said, quite derisively, “Are ye out fer yer little walk tonight, mister?” before driving off in a cloud of dust.

A few years prior to the construction of I-26 in Madison County, which I documented in my book The New Road, an archeological dig uncovered a fluted spear point that was carbon dated to 10,000 B.C. And we, and our neighbors, have found numerous arrowheads and pottery chards on our land after plowing our garden spots next to the creeks. I like to keep those facts in mind when I wrestle with the question, at what point do you really become part of a place? When do you stop being an “ain’t from around here,” a “fereigner,” an outsider, and become the neighbor who “lives up the creek?” Does it take a certain amount of time? Does it take working the soil, burying animals and family in it, stewarding it for the time, however long or brief, you are on it? Does it take thinking about, or representing, a place in one particular way? And for me as an observer, at what point do, or more accurately did, I realize I have the historical understanding and personal connection to this place to honestly and openly represent it in images?

Hard questions, all. And I’m uncertain I know any definitive answers to them. But I do think the definition of what it means to be “of a place” is changing, even in a relatively isolated spot such as Madison County, North Carolina. People have been migrating both in and out of the region forever, some staying longer than others, everyone leaving a footprint on the landscape. I don’t know how one judges one footprint to be more native or true than another.

I suspect our region is one of the most studied places on the planet. Writers, image-makers, ethnographers, statisticians, musicians, and many other “ers” and “ans” have been documenting Appalachia for hundreds of years, myself included. Each of us comes to the work from our own distinct point of view that includes our own baggage. Art engages the personal and the universal. It’s the nature of what artists do. But I’ve often thought that of all the work produced from this region, no writer or documentarian gets it completely right or represents it for the totality of place. But like pieces of a puzzle, when taken together, those individual visions of people and place offer a collective truth that begins to resemble where I live and work.

Rob Amberg November 14, 2012

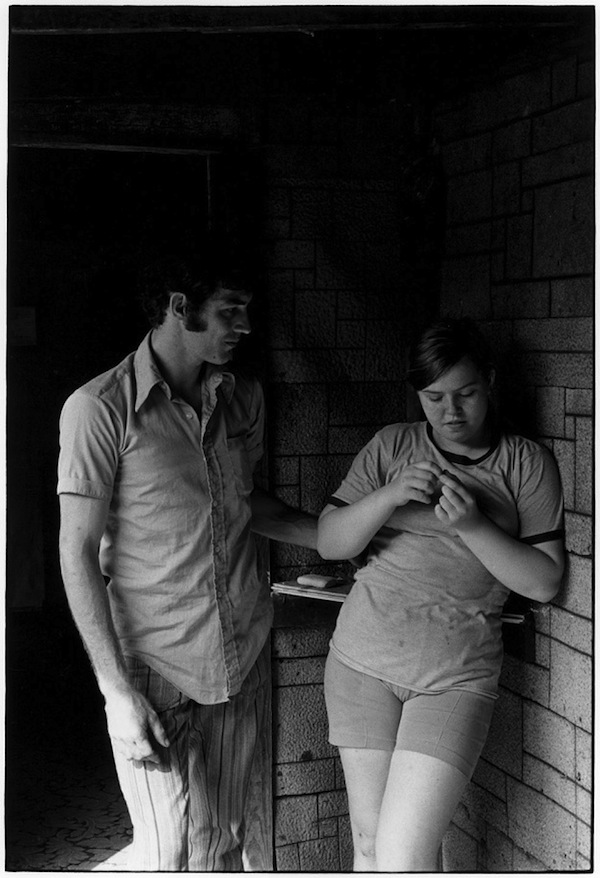

All photographs and essay “Looking for Place” © Rob Amberg. All photographs are from Sodom Laurel Album and The New Road.