I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I’d like to do with my life. More specifically, what I would do if I could do anything. You know, the whole "if you won the lottery, what would you do?" line of thinking. It's hard for me to think about grand ideas or what-ifs like that because I'm too much of a realist, a more practical man. Nonetheless, I dream and I've been known to stay stuck on a dream or two. This has left me with more questions than answers, but the answers I’ve come up with have have been pretty eye-opening.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I’d like to do with my life. More specifically, what I would do if I could do anything. You know, the whole "if you won the lottery, what would you do?" line of thinking. It's hard for me to think about grand ideas or what-ifs like that because I'm too much of a realist, a more practical man. Nonetheless, I dream and I've been known to stay stuck on a dream or two. This has left me with more questions than answers, but the answers I’ve come up with have have been pretty eye-opening.

In short, I want to start a documentary arts center in Williamson, West Virginia. I see a space that combines the likes of Duke's Center for Documentary Studies continuing education curriculum, Whitesburg, Kentucky's Appalshop offerings, and the recently launched interactive documentary, Hollow, directed by Elaine McMillion.

I even know the building I want to use.

I spend a good deal of time in towns like Williamson, Welch, and Bluefield. These towns have incredibly rich histories and you'll find no shortage of available spaces, often historic buildings, that would be the perfect location for something like this.

I envision a space where high school kids can come to learn about photography, filmmaking, or recording audio. I think about members of the community gathering to have their old family photographs scanned and archived. I hear the stories shared from longstanding members of long forgotten places, anxious to tell their stories, to be heard, to not be forgotten. I see folks interested in making pictures, young and old alike, gathered for workshops, for camera walks, learning and growing together.

I said a while back in a radio interview that the people of Appalachia have had a lot taken from them and that I don't just want to be another taker in a long line of takers. I'd like to give something back to the place that has given me so much, that's molded me into who I am. There are so many stories and records that should be recorded and shared, not just in Appalachia, but everywhere. I'm not naive enough to think that I could help everywhere, but I know that my little corner of the world, Mingo County, West Virginia, I could help there. I know that's a place where I can give back.

So, I don't even know who to make this dream a reality, but I'd imagine it going something like this. It's starts with this idea and it grows from there. We'd hold community interest meetings to gauge how folk felt about something like this and how they'd like to see a space and program like this utilized. I’d talk to someone who talks to someone else who knows someone that has a space they'd be willing to offer for a center like this to exist. Grants would be written, connections made, resources made available, and things would begin to take shape. We'd start with a couple of computers, external hard drives, a scanner, and some basic camera equipment.

Maybe it starts with me offering small weekend workshops in Williamson, making the drive up from Raleigh that I’m so familiar with, collaborating with folks and sharing their work in community exhibits. Maybe it starts in a coffee shop.

One of the things I most appreciate about Hollow is the notion that members of the community get to tell their own stories and the story of their place. What a novel concept, right? I mean, who ever thought of "allowing" a group of people to rewrite the narrative about their own place? I'm being sarcastic, of course. Empowering people to tell their own story, enabling them through the use of tools to amplify their voice, and listening. Yes, listening. I think there's a real opportunity to apply the Hollow model throughout Appalachia.

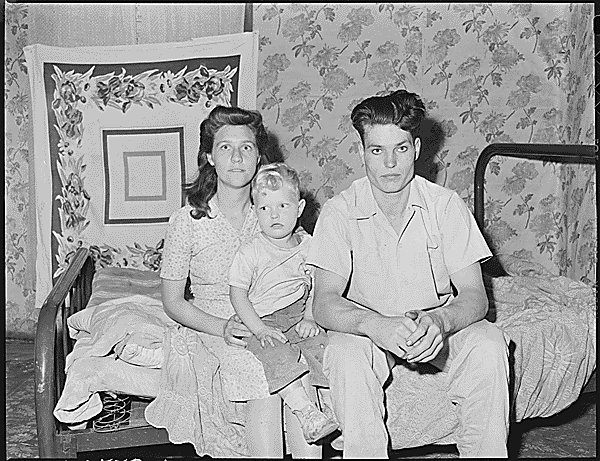

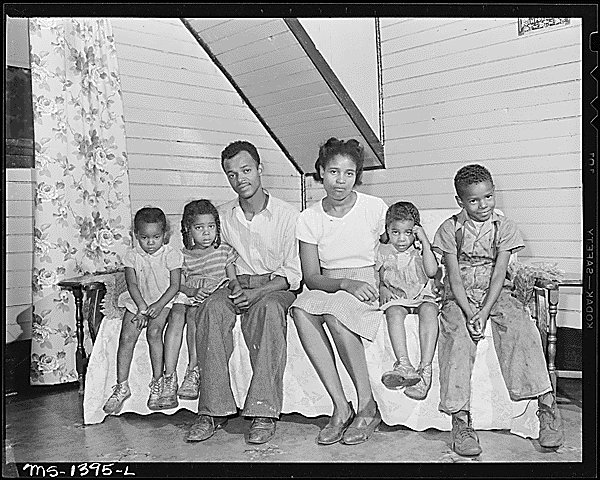

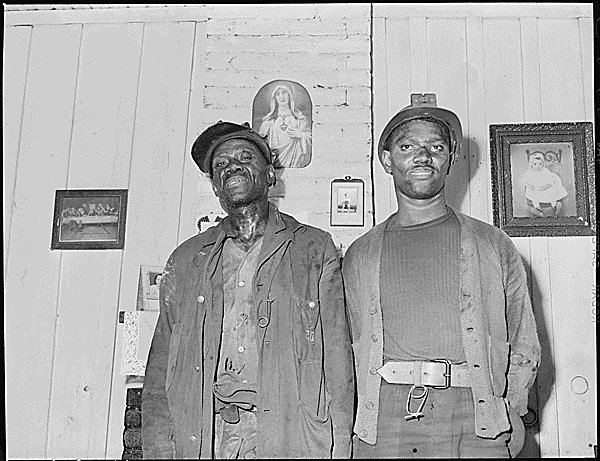

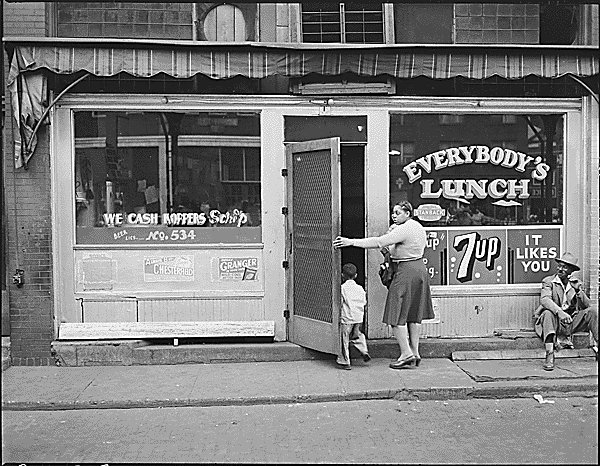

Regarding work made in Appalachia, there's often very little listening and very little community organizing going on and it's been rare that any of it was long-term. Historically, there have been outsiders who drop in only to make pictures of what they wanted to see, pictures that ultimately defined Appalachia to the rest of America: hungry children, broken down cars and shacks, and extreme poverty. Like the coal and timber harvested from the region, pictures were taken, often out of context, and used for someone else's benefit and profit. What does it say to a culture when time and time again they are taken advantage of?

What is their worth?

What is the value of their community?

Who will hear their voice and preserve their stories?

A big influence for my thinking about this process is Huey Perry’s 1972 book They’ll Cut Off Your Project: A Mingo County Chronicle. Perry, a high school teacher in Mingo County during the early years of the War on Poverty, was hired to be the executive director of the newly created Economic Opportunity Commission in 1965. The book offers an amazing account of politics and community organizing in southern West Virginia.

A couple of passages stand out:

Here, Perry talks about the importance of community organizing before writing proposals for grant money from the Office of Economic Opportunity. (It’s important to note that neighboring McDowell County had already submitted an application for a million dollar federal grant before the President had signed the bill or appointed Sargent Shriver to head the OEO, so Mingo County officials were pushing Perry to get a proposal submitted.)

“A community action group would consist of low income citizens organized together to identify their problems and work toward possible solutions. I feel it necessary that we take our time and build an organization that involves the poor in the decisions as to what types of programs they want, rather than to sit down and write up what we think they want. If we do it in the latter way, we will be no different from the welfare department or any other old-line agency that imposes its ideas upon the people.”

Perry goes on:

“If we can change the conditions in Mingo County, perhaps the whole state of West Virginia can be changed. We should work to make this a model for the rest of Appalachia to follow. You know, we are not that much different from eastern Kentucky and other areas of Appalachia.”

I also love this quote from Guy and Candie Carawan’s 1975 book, Voices From the Mountains, by Mike Clark:

“For those of us who are from Appalachia, who love it, and who want to remain, these people offer valuable insights and feelings about what it means to be a mountaineer in a modern technological society. And for the reader who may not live in Appalachia, there is much to be learned here from present attempts within the mountains to build a more democratic society. Welcome to the developing Free State of Appalachia.”

You may say I'm a dreamer...

I can thank Instagram and cell phone photography for leading me to the beautiful analog work of

I can thank Instagram and cell phone photography for leading me to the beautiful analog work of

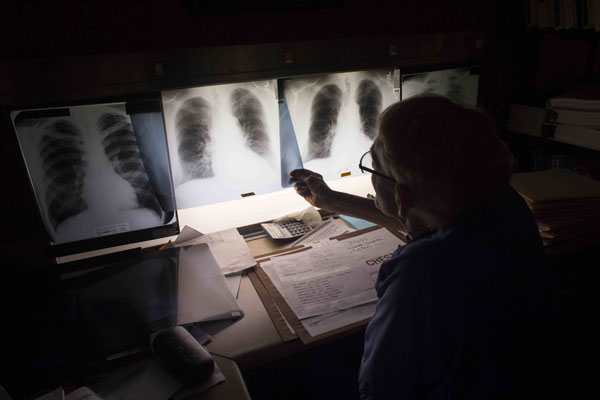

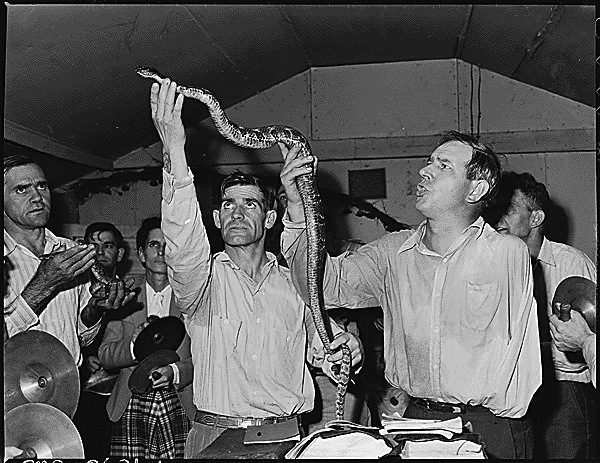

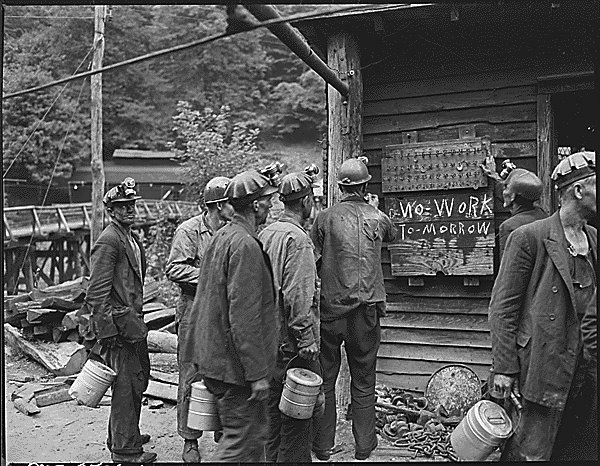

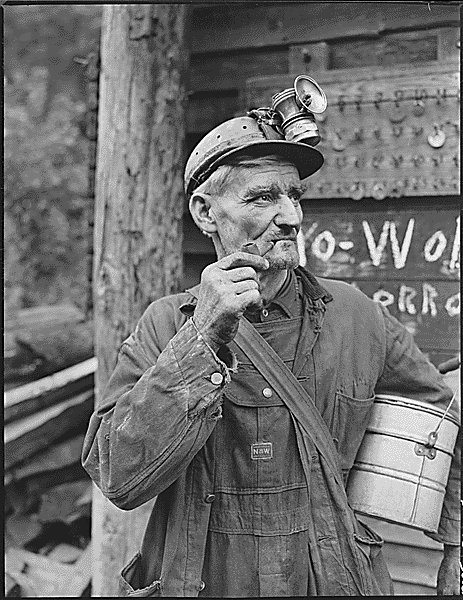

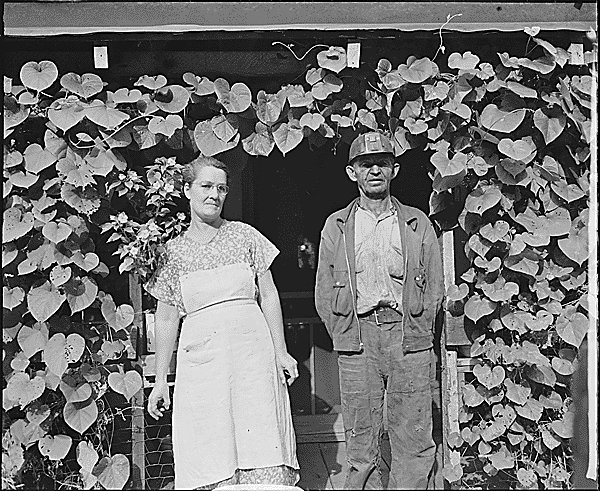

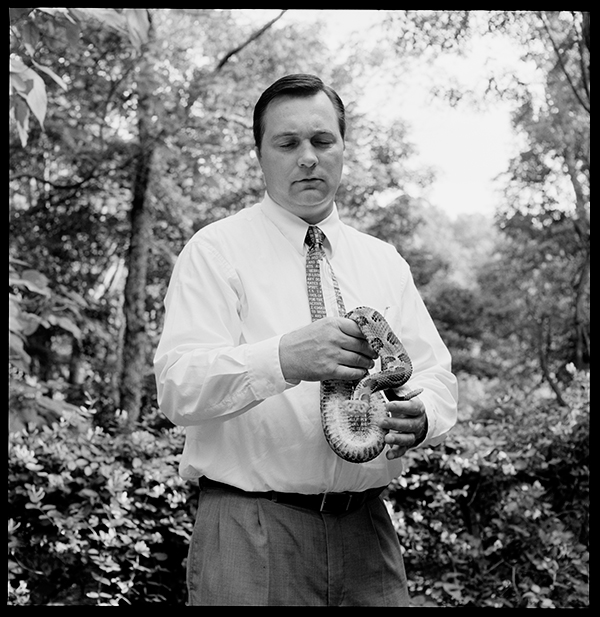

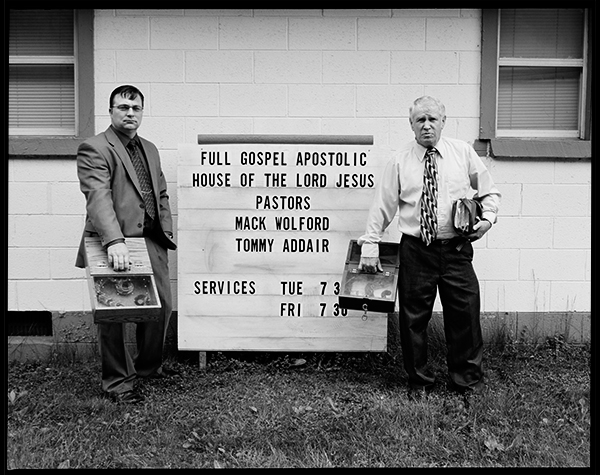

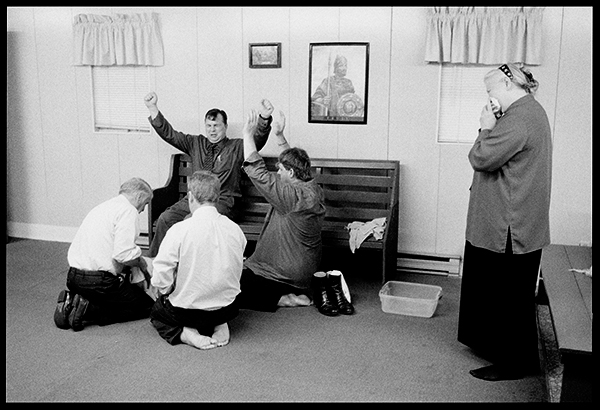

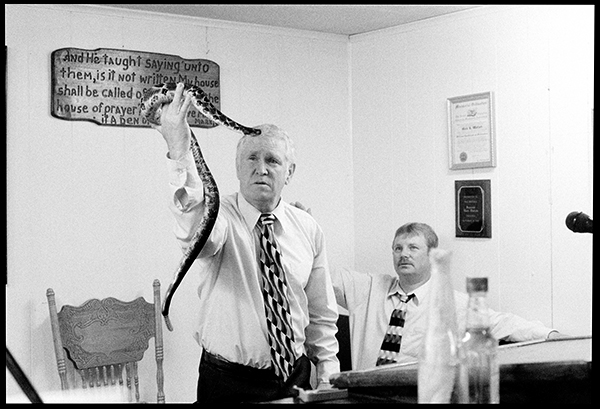

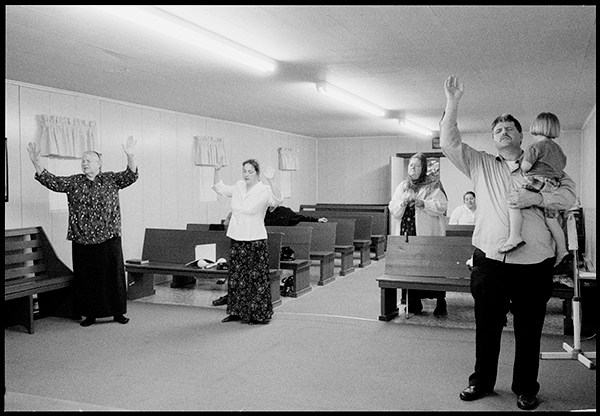

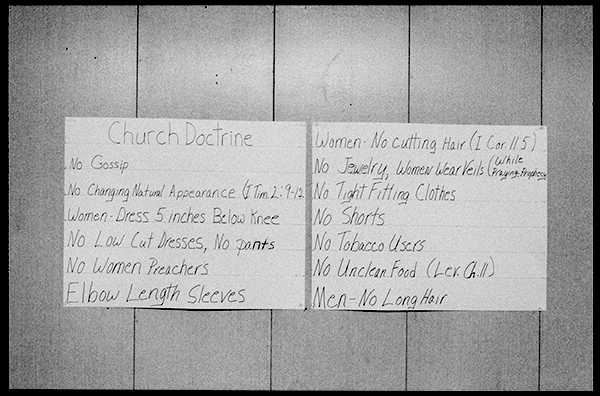

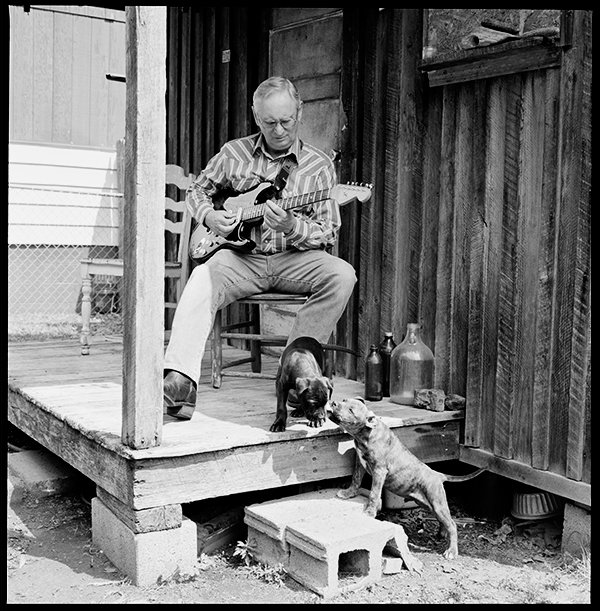

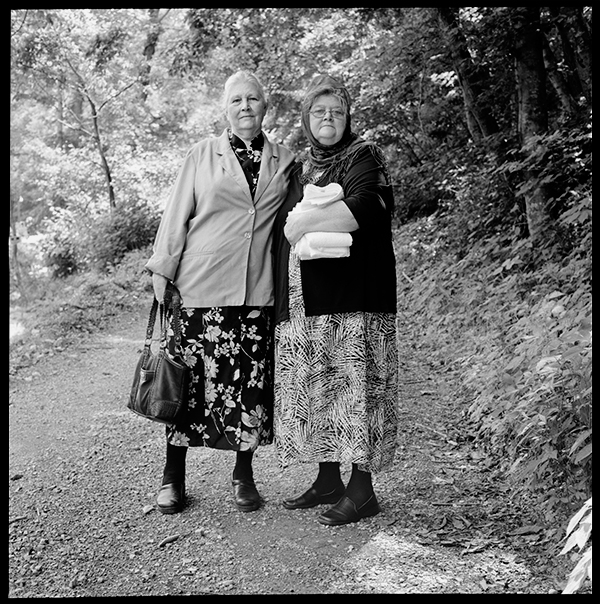

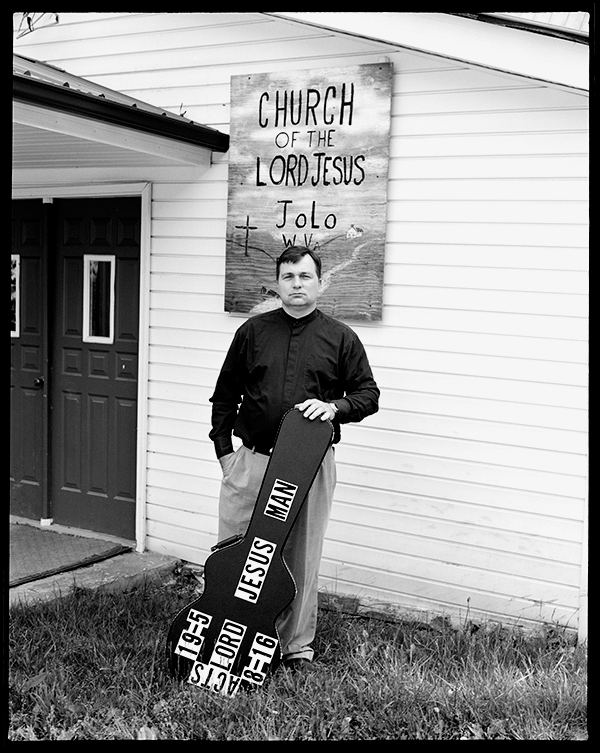

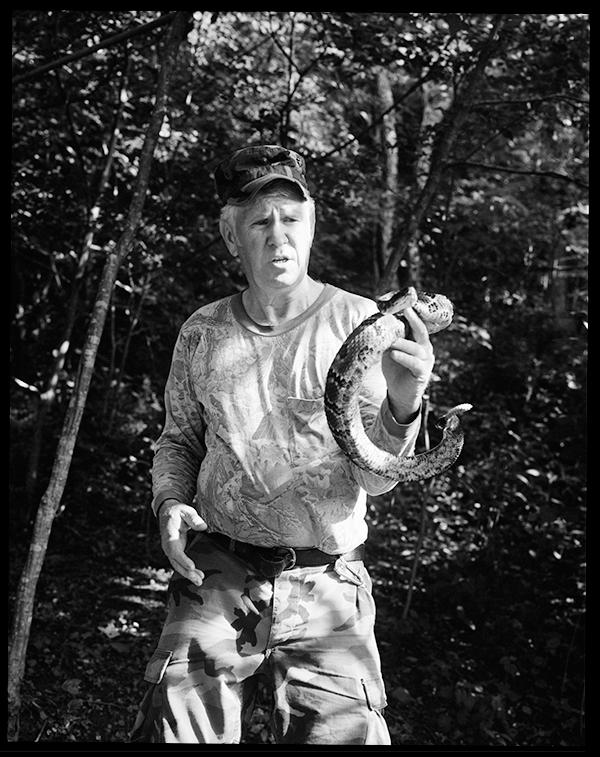

Les Stone is a photographer based in Claryville, New York who has worked extensively in the coalfields of Appalachia as well as Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Kosovo, Liberia, Cambodia, Panama, and Haiti. His images are powerful not only because they bring to our attention important and often overlooked people and events, but because they do so in a visually arresting way. You can see more of his work

Les Stone is a photographer based in Claryville, New York who has worked extensively in the coalfields of Appalachia as well as Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Kosovo, Liberia, Cambodia, Panama, and Haiti. His images are powerful not only because they bring to our attention important and often overlooked people and events, but because they do so in a visually arresting way. You can see more of his work