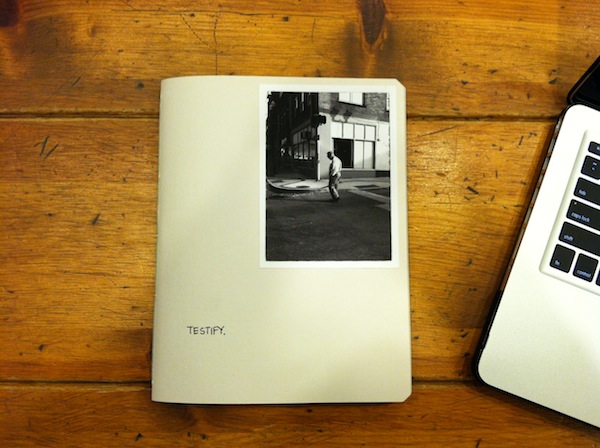

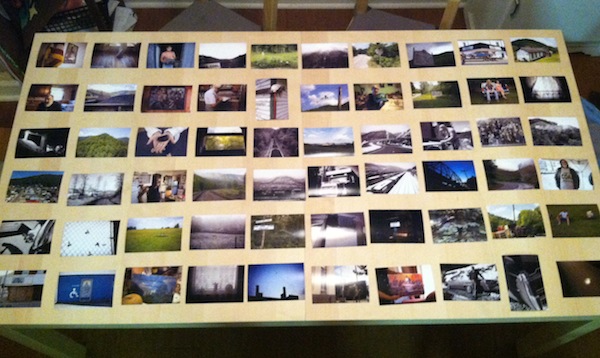

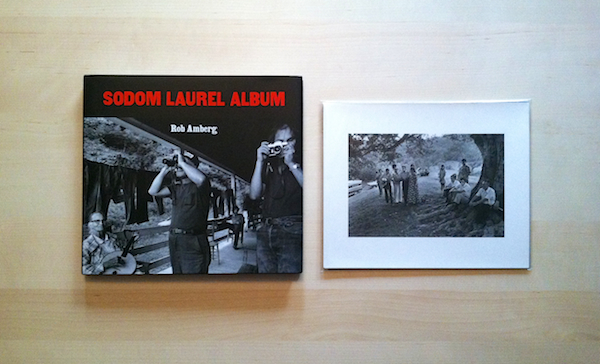

So, my portfolio site is experiencing technical difficulties. While I'm in the process of rebuilding it, I wanted to share my Testify project statement as well as another look at the book dummy I'm working on. Thanks for your patience and I'll let you know when my portfolio site is up and running again.

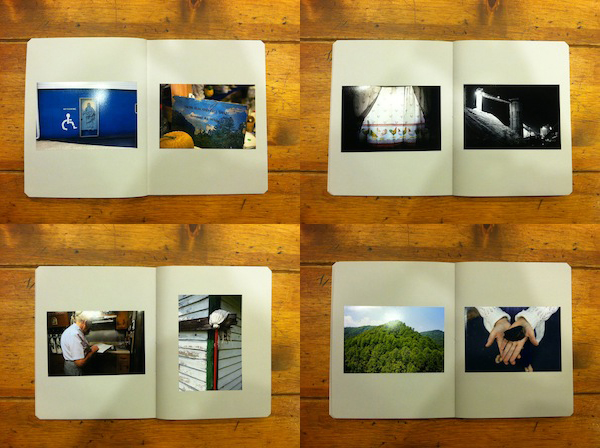

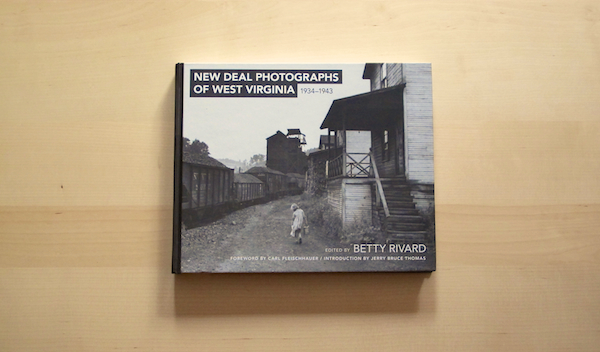

Testify is a visual love letter to Appalachia, the land of my blood. This is my testimony of how I came to see the importance of home and my connection to place. After moving away as a teenager, I’ve struggled to return, to latch on to something from my memory. These images are a vignette into my working through the problem of the construction of memory versus reality. My work embraces the raw beauty of the mountains while keeping at arms length the stereotypical images that have tried to define Appalachia for decades.

The word ‘testify’ carries both a religious and legal meaning. In the pentecostal holiness churches of home, a portion of time during a church service is devoted to allowing members to share publicly what God has done in their lives; their testimony. In legal terms, one’s testimony is a statement accepted, sworn under oath, believed to be true and acceptable.

I am both an insider and an outsider and though I maintain a safe distance in my photographs, I attempt to invite you into the intimacy of family, of sacred space. Testify is my bearing witness of a personal journey, of never truly being able to go home again, to seek answers from my ancestral home. Appalachia testifies of timelessness and natural beauty. The mountains testify of protection and sanctuary and at the same time the horrible destruction of mountaintop removal mining. The people of Appalachia testify of their pride and resilience. Old time religion testifies of the power in the blood and a heavenly home just across the shore.

My grandfather told me that I have two ears and one mouth, which means that I should listen twice as often as I speak. Through these images, I’ve tried to do just that - to listen more than I speak, both with my voice and my cameras. These images arise out of my pride of where I am from and where I am of, and an enduring love for Appalachia.

This is my testimony.