Les Stone is a photographer based in Claryville, New York who has worked extensively in the coalfields of Appalachia as well as Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Kosovo, Liberia, Cambodia, Panama, and Haiti. His images are powerful not only because they bring to our attention important and often overlooked people and events, but because they do so in a visually arresting way. You can see more of his work here.

Les Stone is a photographer based in Claryville, New York who has worked extensively in the coalfields of Appalachia as well as Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Kosovo, Liberia, Cambodia, Panama, and Haiti. His images are powerful not only because they bring to our attention important and often overlooked people and events, but because they do so in a visually arresting way. You can see more of his work here.

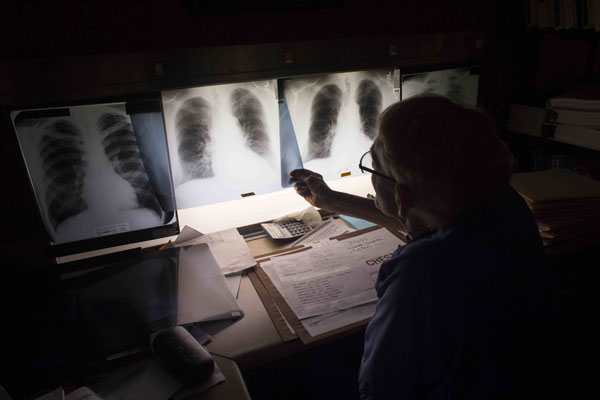

Les and I got in touch via Facebook, which eventually led to a phone call. It was clear to me from the outset that he was deeply moved by what he saw in Appalachia. The outrage in his voice about miners suffering from black lung disease, his primary focus in West Virginia, was palpable. The passion I heard on the phone is easy to see in his photographs. I asked Les to write an essay to accompany some of his work from Appalachia.

Deep in the Heart of Appalachia

McDowell County, West Virginia is one of the poorest and most remote counties in the United States. Because of coal mining, Welch, had at one time the highest concentration of millionaires in the United States. When I drive down these two lane mountain roads, it feels like another world, far away, perhaps another country, certainly not the wealthiest country on the face of the planet, the USA. For those of you who have never been here, it is truly a special experience and forget all the stupid hillbilly jokes; there are real and great people here with real problems and we are all part of each other’s lives.

Thousands of immigrants from Europe came to find work in the coalfields of Appalachia, to Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky to name a few. Welch, the county seat of McDowell, is scarcely a shadow of it's former self, but still today more coal is taken out of this area than any time in its history. Mechanization and non-union mining has caused this area has become almost destitute, not to mention that many of these companies have treated the people here with ethical disdain and criminal and moral neglect since the beginning of mining here. Domestic wars have been fought here and hundreds, even thousands, have died in mining accidents and during strikes. Labor history was made here in Appalachia that affects all Americans today.

Black lung, heart disease, diabetes, and drug abuse are endemic in Appalachia. Black lung disease is on the rise among all the miners. Many of formerly wealthy towns in the area are now little more than ghost towns and most of the coal camp towns have fallen into complete poverty. Yet, still to this day the only jobs that pay more than minimum wage are the most dangerous jobs in the world, coal mining. These few jobs are greatly coveted and coal mining, down through the generations, is as so many people have told me again and again, “in our blood.” I’ve met sons who have left the area, gone to college, got an education and come back to mine coal. Mining is not only in the blood, it still pays more than any other job they could potentially get anywhere else. Generations of families have survived and prospered from coal mining.

Few people here have health insurance and or easy access to clinics. Life in many parts of Appalachia almost appears to me to be at third world levels of poverty. It's incredibly difficult, yet Appalachian people are some of the proudest, kindest people I’ve ever met.

In the context of a world economy from which we are all suffering, some of our fellow countryman have had it a lot worse for a long time and they should not be forgotten. In fact, they need to be celebrated as heroes; they're the reason the lights are still on. I don't say that to celebrate coal. We need to find less polluting alternatives and quickly, but as in all decisions involving policy you can't forget that people's lives are deeply affected and directly impacted by those decisions.

Many of these men dying of black lung disease live out the remainder of their lives in pain and heartbreak with little faith left in either the coal companies or the government that has neglected them. Their eyes have been wide open their whole lives. They know what’s possibly in store for them and they know they’re sacrificing their health for family and they do it proudly. Many are bitter, and rightfully so, about how they are treated after no longer being able to work long hours at hard labor in terrible conditions. Most of us wouldn't work underground no matter what the pay is.

All of these people have so many stories, so profound that I can say that I am greatly challenged as a photographer and storyteller. I can only scratch the surface of their lives and every time I plan a trip back, I make the calls and find out another person has died since I was last with them. I’ve never been so stirred by my work.

I did not grow up in Appalachia. My experiences are completely different and I don’t know what difference I can make for me or anyone and maybe that’s the point. I feel better personally meeting and knowing these incredible people and I think they feel the same. For me, photography is a form of immortality, always living when everyone is gone.

Les Stone April 2013

All photographs and essay “Deep in the Heart of Appalachia” © Les Stone.

CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WINNER – CAROLYN PARKER!

CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR WINNER – CAROLYN PARKER!

Hey folks! I'm excited to announce the launch of my

Hey folks! I'm excited to announce the launch of my  My friend Cindy Shepherd from Oneida, Kentucky posted a poem on Facebook a few days ago, which was an exercise she planned to do with a group of elementary school children. After reading it, I was moved and inspired to write my own version of 'Where I'm From.'

My friend Cindy Shepherd from Oneida, Kentucky posted a poem on Facebook a few days ago, which was an exercise she planned to do with a group of elementary school children. After reading it, I was moved and inspired to write my own version of 'Where I'm From.'