Jeff Rich is a photographer and educator based in Iowa City, Iowa. His long form project, The Watershed Project, first caught my attention a few years back when I learned of it via Photolucida. Rich also curates the 'Eyes on the South' photo blog for Oxford American. We spoke a while back about featuring some of his work here and he was also kind enough to answer a few questions in the midst of a busy summer. Thanks, Jeff!

Jeff Rich is a photographer and educator based in Iowa City, Iowa. His long form project, The Watershed Project, first caught my attention a few years back when I learned of it via Photolucida. Rich also curates the 'Eyes on the South' photo blog for Oxford American. We spoke a while back about featuring some of his work here and he was also kind enough to answer a few questions in the midst of a busy summer. Thanks, Jeff!

Clearly the issues addressed in Watershed aren't unique to Appalachia. Nationwide, worldwide, people are working to protect watersheds from issues like runoff and loss of habitat. Working specifically in Appalachia though, did you face unique cultural or environmental challenges?

Working in Western North Carolina was the first time I had really researched and documented issues like these. However throughout my research I have learned a lot about watershed management. As you say most of the issues faced here are the same in every watershed. I intentionally focused on these problems because in many ways the French Broad can be seen as a microcosm of much larger watersheds, like the Mississippi River Basin. As for being unique, the Central Appalachian mountains are one of the most biologically diverse regions in the country. Culturally there were no challenges, I found that people in the watershed were very interested in keeping the river clean and livable.

I know as a kid growing up on the Tug River, which separates West Virginia and Kentucky, I always saw polluted creeks and streams. Part of what I saw were remnants from flooding and the trash left behind, but it wasn't uncommon to see folks just pitch their garbage over the riverbank. It was sort of like the concept of throwing something "away" meant pitching it into the river and letting the river carry it away. Did you see any evidence of this mindset in the areas of North Carolina and Tennessee you worked in? I'm just curious as to whether it's more of an isolated mode of thinking or if it's more common than that in mountain communities.

One of the reasons I started this project was to document the visual effects of this mindset that the river is our toilet. Evidence of this can be found throughout the region, and when I first started this work I focused on that pretty heavily. I found that it is a problem throughout the region, whether it is in the big cities or smaller communities. However, on the flip side of this is the progress that this area has made over the past 40 years. The French Broad River is much cleaner now than it ever was in the past 60 years. I find that people are much more aware of what is upstream of them because of pollution in their towns. Consequently residents awareness is much higher now of what is downstream.

You're work reminds me that it isn't just the mountains that make Appalachia what it is, it's also the water. Can you talk a little bit about the relationship between the two and how your work incorporates these visual elements?

I've heard it said that the French Broad River is the third oldest river in the world, and that it is even older than the Appalachian mountains that surround it. With the birth of the Appalachians at about 480 Million years ago, I find this geologic history inspiring. One of the things I wanted to do with this work was really document this moment in this history. How do we effect this landscape which has a lifespan that really dwarfs our own history? Especially in post-industrial terms, in this time-scale we have only just started to effect the landscape in significant ways. Because of the topography of the area, many of the cities have water running right through the middle of town. These rivers have formed the valleys where most people live. I found that some of the towns embraced the rivers and creeks, while others ignored them. This relationship with the rivers forms the visual base of much of my work in the watershed.

There's an unmistakable beauty in your work, which requires the viewer's gaze. The image of the Blue Ridge Paper Mill comes to mind. Can you talk a little about what's going on (i.e. there's this really arresting photograph, bathed in perfect light, rich color, yet it's a paper mill releasing all sorts of chemicals into the air and no doubt the water)? This is something you're putting in front of the viewer and asking them to deal with right?

Yes, absolutely. I want the viewer to have a similar experience to my own when I first encountered the mill. I experienced what I have heard called an industrial sublime. In other words I was awestruck in the face of industry. I find this fine-line between beauty and the environmental reality of the situation is a fascinating thing to document.

I returned several times to photograph the plant over the span of about three years and each time I am amazed at how the mill dominates the valley. Each time I returned to the mill to photograph it, I ended up with images that described the appearance and size of the mill, but I never captured an image that portrayed the effect of the mill on the surrounding landscape. The effect of the mill was what I was most interested in, since this mill was one of the largest polluters of the area for most of the 20th century. The Pigeon River which runs right through the center of the plant was used for all of their waste water and as a result was heavily polluted, negatively effecting downstream communities all the way to Newport, Tennessee.

How do you see the final project being put out into the world? Three separate books under the umbrella of Watershed?

Yes, the Watershed project is ongoing. I am following the water all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico, via the Tennessee River, and finally the Mississippi River. The ultimate goal is to have the work in three separate books. Currently I'm documenting the TVA's (Tennessee Valley Authority) effect on the region. The TVA was the largest New Deal project and had an enormous impact during the twentieth century. I have also started documenting flood control measures taken by the Army Corps of engineers along the Mississippi River.

I have created an interactive project website that maps the rivers and photographs and gives a bit more background information. which can be seen at watershed-project.com.

Most of the environmental issue portraiture about Appalachia that exists today is about mountaintop removal coal mining. I don't see your work as a break from that, but rather a supplement to raising awareness of what's going on in these ancient hills. Can you talk about that?

I think that mountaintop removal is one of the biggest issues facing the region. Doing a project like Watershed is definitely about raising awareness, not only of current exploitation of resources, but also showing what's at stake. I think that's what is most important to me, showing the problems, but also showing what we could possibly lose in the process.

1. Blue Ridge Paper Mill, Pigeon River, Canton, North Carolina, 2008

2. Bridge Reconstruction - The French Broad River, Marshall, North Carolina, 2006

3. River Clean-up on the Swannanoa River, Asheville, North Carolina, 2007

4. Cement Plant, Asheville, North Carolina, 2006

5. Benjamin and Katie, French Broad River, Asheville, North Carolina, 2008

6. Garden, North Toe River, Spruce Pine, North Carolina, 2007

7. Foam from upriver pollution, Pigeon River, Tennessee, 2007

8. Crossing, Swannanoa River, Asheville, North Carolina, 2005

9. Toe River, North Carolina, 2007

10. Mitch and Mike, The French Broad River, Stackhouse, North Carolina, 2007

11. Brown family farm, North Fork of the Swannanoa River, Black Mountain, North Carolina, 2007

12. Ski Lift, Little Pigeon River, Gatlinburg, Tennessee, 2007

13. Barber Orchard Superfund Site, Waynesville, North Carolina, 2007

14. TVA South Holston Dam, South Fork Holston River, 2012

15. South Holston Weir Dam, South Fork Holston River, 2012

16. Calderwood Lake, Little Tennessee River, Vonore, Tennessee, 2012

17. Road to Nowhere (North Shore Road) Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee, 2012

18. Fort Patrick Henry Dam, South Fork Holston River, Kingsport, Tennessee, 2012

19. Forest Fire and I-24, Mill Creek, Whiteside, Tennessee, 2011

20. Fish Kill, Cumberland Fossil Plant, Lake Barkley, Cumberland City, 2011

21. Raccoon Mountain Pumped Storage Plant Outflow, Tennessee River, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 2010

22. Watts Bar Nuclear Plant, Tennessee River, 2010

23. Glenn on his dock, Coal Fly Ash Spill, Kingston, Tennessee, 2009

24. Coal Fly Ash Spill, Harriman, Tennessee, 2009

All photographs © Jeff Rich.

UPDATE: We have a winner!

UPDATE: We have a winner!

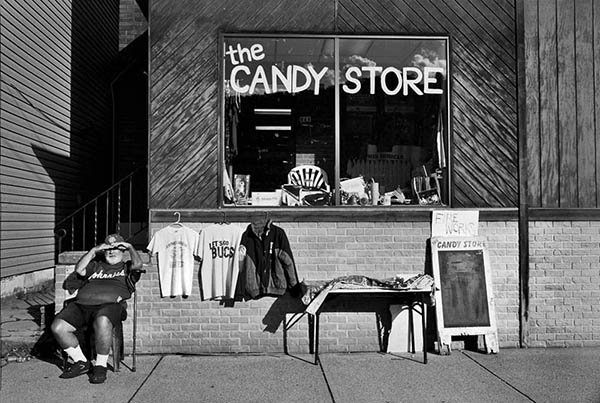

SEEN AND FELT: Appalachia, 2012

SEEN AND FELT: Appalachia, 2012

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I’d like to do with my life. More specifically, what I would do if I could do anything. You know, the whole "if you won the lottery, what would you do?" line of thinking. It's hard for me to think about grand ideas or what-ifs like that because I'm too much of a realist, a more practical man. Nonetheless, I dream and I've been known to stay stuck on a dream or two. This has left me with more questions than answers, but the answers I’ve come up with have have been pretty eye-opening.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I’d like to do with my life. More specifically, what I would do if I could do anything. You know, the whole "if you won the lottery, what would you do?" line of thinking. It's hard for me to think about grand ideas or what-ifs like that because I'm too much of a realist, a more practical man. Nonetheless, I dream and I've been known to stay stuck on a dream or two. This has left me with more questions than answers, but the answers I’ve come up with have have been pretty eye-opening.